〜The final conclusion of "sustainable cities" that we should discuss now, during peacetime〜

*This article is based on publicly available data and estimates as of December 2025.

"It is not the strongest that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives; it is those who are most adaptable to change."

These words, said to have been left by Charles Darwin, the father of evolution theory, sharply capture the "brutal reality" that modern Japanese cities face.

In the past, during Japan's period of rapid economic growth, recovery from disasters was synonymous with "returning things to their original state." The population continued to grow, and the economy was on an upward trend. That's why rebuilding houses in the same places as they were destroyed and rebuilding roads was the most rational and unquestionably correct response. However, times have completely changed.

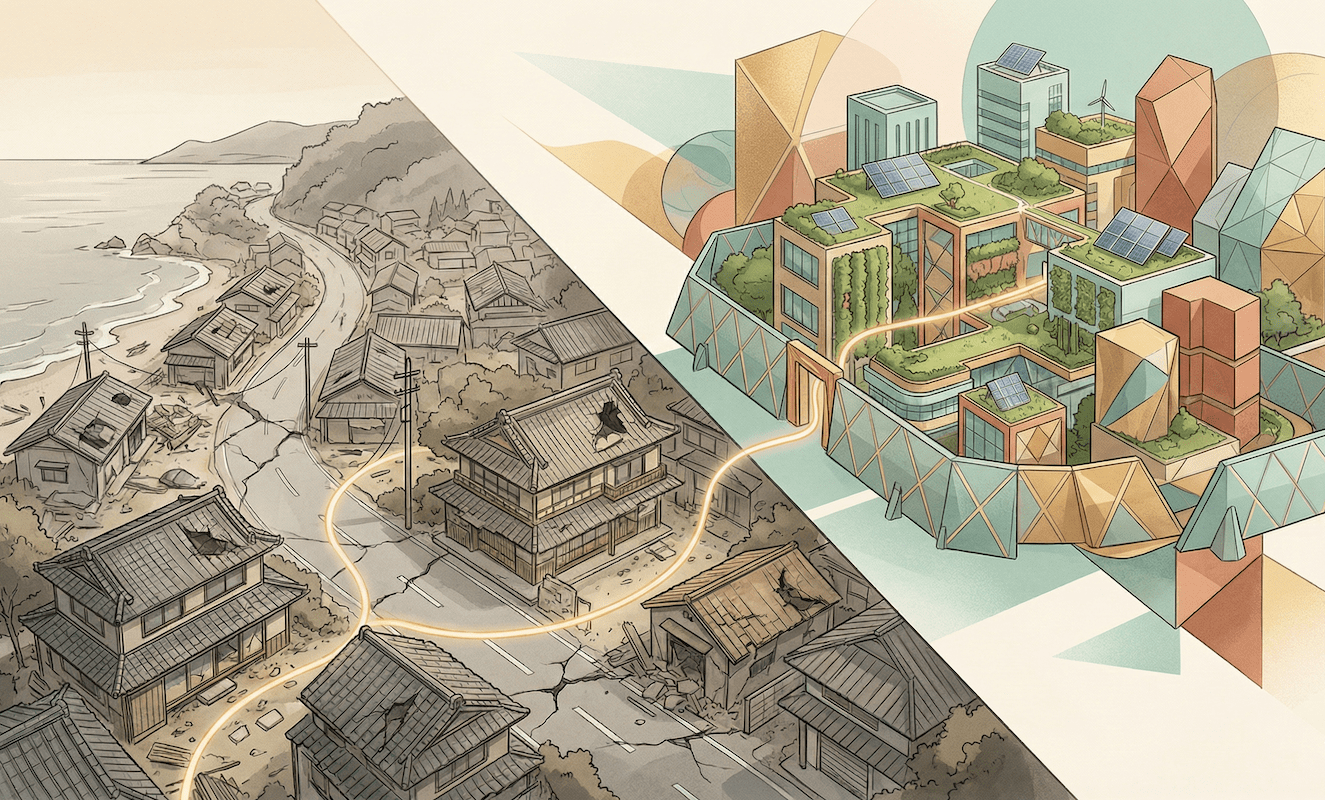

The devastating earthquake that struck the Noto Peninsula on New Year's Day, 2024, was more than just a natural disaster; it exposed an "inconvenient truth" that Japanese society had long put off: in a region where population decline and an aging society have reached their peak, it is financially and socially impossible to apply the old reconstruction model.

Will it be a revival, a strategic retreat, or something in between: smart downsizing?

In this article, we will compare and analyze the current situation in Noto with advanced reconstruction examples from overseas, such as New Zealand and Italy, and also delve deeply into the ``disasters and urban sustainability'' that we must choose in the future, incorporating the efforts of Toyako Town in Hokkaido.

1. The definition of "reconstruction" has changed: What is the global standard for "Build Back Better"?

Japan's postwar success story and its structural limitations

First, let's look at the historical background we all need to share as a premise. The Disaster Relief Act, which forms the basis of Japan's disaster recovery legislation, was enacted in 1947 (Showa 22). During the chaotic period following the war, this law focused on "relief" to guarantee food, clothing, and shelter for the time being, and its basic goal was to "restore the status quo."

The Ise Bay Typhoon in 1959 prompted the enactment of the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act, but this act also focused on "defense" through the development of infrastructure, and the perspective of "urban development" was weak. This was because at the time, "if you build it, people will come."

However, this paradigm collapsed after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995 and the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011. This was because we were faced with the reality that "returning things to their original state will lead to more deaths." This led to the concept of "Build Back Better," which was adopted at the Third United Nations World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction (Sendai) in 2015.

In other words, disasters should be seen as an opportunity to update the town's operating system and redesign social systems to be safer and more sustainable than before. This is the modern global standard.

2. Noto faces population loss and financial challenges

The shock of over 4,000 people disappearing in six months

So, is it easy to "Build Back Better" in modern Japan? The 2024 Noto Peninsula earthquake shows us, in brutal numbers, how difficult it is.

According to estimates based on the resident basic register published by Ishikawa Prefecture, the population of the six cities and towns in Oku-Noto (Wajima City, Suzu City, Noto Town, Anamizu Town, Nanao City, and Shika Town) decreased by approximately 4,384 people in just seven months (January to August 2024) after the disaster. This figure includes natural attrition (deaths, etc.), but also includes "social outflow" that far exceeds the average annual decline.

[Figure 1] Population decline in six cities and towns in Oku-Noto (seven months after the disaster)

*Created based on Ishikawa Prefecture statistical information and data published by each local government

In particular, in areas where the aging rate exceeds 50%, if the disruption of infrastructure continues for a long period of time, people who require medical care or nursing care will have no choice but to evacuate outside the area. Furthermore, the reality is that young people and those raising children who have left the area are extremely unlikely to return to their hometowns, which will take several years to recover. In sociological terms, this is sometimes called "population evaporation."

2.6 trillion yen in damage and the taboo of "selection and concentration"

Furthermore, financial constraints weigh heavily on the government. According to estimates by the Cabinet Office, the damage to properties such as homes and factories caused by the Noto Peninsula earthquake alone amounted to approximately 2.6 trillion yen. In response, the "Noto Creative Reconstruction Support Grant" framework initially prepared by the government was launched with a budget of several tens of billions of yen.

Now, a debate that was once considered taboo in government circles is beginning to take on a more realistic tone: to what extent should huge amounts of public money be spent to fully restore infrastructure in marginal villages that are likely to become deserted in the future?

Unfortunately, Japan's current finances do not have the financial strength to completely reconstruct all roads and water pipes, even deep in the mountains. We are now faced with an extremely difficult choice between the emotional justice of "reconstruction without abandoning people" and the cold reality of "sustainable fiscal spending."

3. Global Answers: A Comparative Analysis of New Zealand and Italy

Let's now turn our attention to examples from overseas. How have countries that have experienced similar large-scale disasters responded to this "reconstruction dilemma"? We will compare the models of New Zealand (Canterbury earthquake), Italy (L'Aquila earthquake), and Japan.

| Comparison items | [Japan (Noto, Eastern Japan)] Consensus building and local reconstruction |

[New Zealand (Christchurch)] Top-down purchase and transfer type |

|---|---|---|

| land use decision | In principle, residents' consent is required. Designating dangerous areas and mass relocations take a huge amount of time to reach consensus, and this tends to lead to population outflow during that time. |

Government agencies made a quick decision. The CERA (Coronavirus Reconstruction Agency) designated "red zones (no residence allowed)" based on scientific evidence. This was a powerful top-down approach. |

| Financial support | Public assistance plus self-reconstruction. The maximum amount of aid of 3 million yen is not enough to cover the cost of reconstruction, and many victims are left in the difficult situation of having to take on "double loans." |

Purchase by the government at market value. The government offers to purchase land at pre-disaster market prices, allowing disaster victims to obtain cash and move to new areas quickly. |

| Reconstruction speed | Long term (10 years). Because of the emphasis on careful processes, there are many cases where residents do not return once the infrastructure development is complete. |

Extremely quickly (a few years). Four years after the purchase offer was made, more than 951 TP3T of the eligible people had completed relocation and rebuilding their lives. |

*The data in the table is a comparative summary based on each country's recovery reports and public documents (Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism documents, etc.).

The impact of New Zealand's "red zone" policy

The New Zealand case in particular is extremely drastic from a Japanese perspective. They designated areas with a high risk of liquefaction as "red zones" and made them off-limits to residents, and the government then used force to buy up the land.

While this may seem forceful at first glance, it had the clear benefit of providing disaster victims with an economic exit strategy. Unlike Japan, where the decision of whether to stay or leave is left to the individual's discretion and financial ability, the government declared, "You can't live here. Instead, we will provide financial compensation," allowing disaster victims to move on to the next step in their lives without hesitation.

On the other hand, after the 2009 L'Aquila earthquake in Italy, the government led the construction of a huge new town (CASE project) on the outskirts, but this backfired. The problem of "lack of social sustainability" was raised, with elderly people cut off from the historic old town, losing their community and becoming plagued by loneliness. This is a lesson that building only the infrastructure does not necessarily lead to people's hearts.

4. Hope for Japan: Pre-disaster reconstruction seen in Toyako Town, Hokkaido

Urban development based on "X-Day"

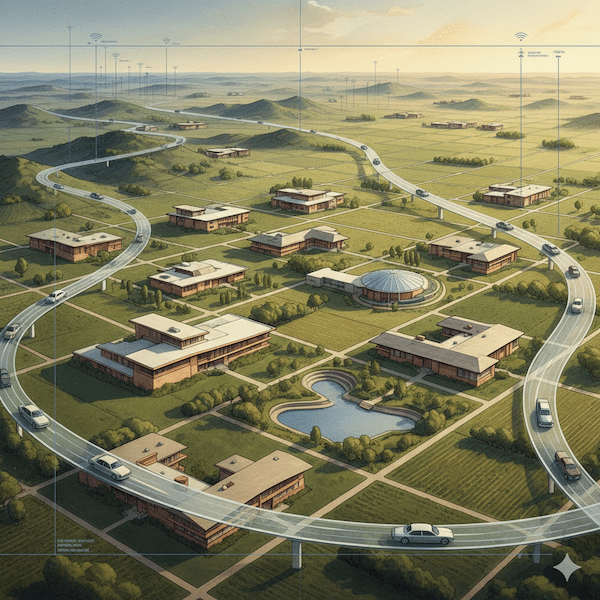

There is a region in Hokkaido called Toyako Town that is exploring "optimal solutions" in a uniquely Japanese context while taking into account examples from overseas.

While the town is a scenic tourist destination, it is also destined to coexist with Mount Usu, an active volcano that erupts every 20 to 30 years. While the Noto earthquake was an unexpected blow, Toyako Town is developing the town with the conviction that the next eruption will definitely come. In technical terms, this is called the idea of "pre-recovery."

During the 2000 eruption, not a single person was killed thanks to a hazard map prepared in advance and prompt evacuation instructions. This was not only a wonderful humanitarian achievement, but also had enormous economic significance. Because there were "zero human casualties," the brand image of the area as a "safe tourist destination" was maintained, and tourism was able to resume just a few months after the eruption ended.

The "strength" of monetizing disaster ruins

Another unique feature of Toyako Town is that it has chosen not to repair the remains of destroyed roads and apartment buildings, but has instead preserved them as they are. These have been developed as key features of the Toyako-Usuzan Geopark, and are a source of attraction for educational trips and foreign tourists.

Rather than sealing away disasters as dreadful memories, we can turn them into learning opportunities as a reminder of the Earth's vitality, and turn that into tourism revenue to recoup disaster prevention costs. This ecosystem that links the economy and disaster prevention could be said to be one sustainable model for an era of declining population.

5. Conclusion: The "social contract" in peacetime will determine the future

Consolidation (compact city)

■ Optimizing infrastructure costs

By consolidating scattered villages into central areas, maintenance costs for roads and water supply can be reduced, and the saved funds can be used for medical care and welfare.

■ Elimination of physical risks

By permanently withdrawing (resetting) from dangerous areas, the risk of future disasters is physically reduced to zero.

Local residence/inheritance

■ Maintaining the community

A social safety net that protects connections with neighbors and prevents elderly people from becoming isolated or dying alone.

■ Respect for identity

Protecting ancestral land and festivals is a spiritual pillar for the residents and cannot be measured by simple economic rationality.

As shown in the diagram above, there is an eternal conflict between "efficiency" and "humanity" in disaster recovery. There is no magic wand that can resolve this conflict. However, the lessons that can be learned from Noto and other examples around the world are clear.

The point is, "If we start discussing this after a disaster has occurred, it will already be too late."

In the chaos immediately following a disaster, it is impossible to calmly discuss whether or not to close down a community. That is why, while we are still in peacetime, we must face the inconvenient truth of the shrinking of our community and the risks involved, and reach a consensus on how to reconstruct (or end) this town in the event of an emergency.

The map of the future is not drawn by someone else.

It is something we "choose."

In Japan, where the population is declining and the economy is shrinking, "returning to pre-disaster conditions" would mean nothing more than paving the way for a gradual decline. What is needed is a new social contract that determines the size and how we will maintain our towns, including painful "withdrawal" and "consolidation."

Only a town that is unafraid of change, that faces reality squarely, and that prepares in peacetime will be able to leave its mark on the map for the next generation. We have a responsibility to begin this discussion now, so that the tragedy of Noto will not be in vain.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism "Guidelines for Advance Preparation for Urban Reconstruction"

- Cabinet Office Disaster Prevention Information Page (Passing on Disaster Lessons)

- Ishikawa Prefecture Creative Reconstruction Plan (tentative name) Outline

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.