〜The "spiral" structure that supported Edo, a city of one million people〜

*This article is based on survey information as of January 2026 and the latest urban planning theory.

It is said that the shape of a city embodies the very "ideology" of that civilization.

For example, think of the colonies of ancient Rome or the Heijo and Heian capitals of Japan. There, we can see the orderly "grid" structure that symbolizes authority and order. Similarly, the "concentric" defensive walls seen in medieval European walled cities also represented a strong determination to separate inside from outside.

However, the city of Edo, conceived by Tokugawa Ieyasu and completed over the three generations of Hidetada and Iemitsu, adopted a strange and organic geometry that set it apart from the conventional wisdom of the world.

In other words, the moat and town spread out in a spiral around the central keep of Edo Castle."No"-shaped (spiral) structureis.

Why did Edo choose a complex spiral instead of an easier-to-manage grid? Was it simply a geographical constraint? No, a highly calculated strategy for "dual use of military and economic power" was hidden behind it.

This paper thoroughly elucidates how this spiral structure functioned as a logistics infrastructure supporting the lives of a city of one million people. It then proposes a concrete "Neo-Edo model" that applies this systems theory insight to urban development in modern-day Hokkaido, particularly in Toyako Town, which is facing population decline and financial challenges.

1. Strategic Geometry: Why the "no" Shape?

The limits of the grid and the infinity of the spiral

First, we will analyze the uniqueness of Edo from the perspective of urban design. Generally, the defensive lines of a walled city are classified into two types: a concentric pattern known as the "outline style" and a parallel pattern known as the "connected wall style."

However, the concentric city model had one fatal flaw in urban planning."Limits to Growth"As a city grows, the moment its population exceeds the capacity of its outer walls, the existing walls become an obstacle and prevent further expansion. To expand, the city must destroy the walls and build a new closed system on the outside, at great expense.

The spiral structure adopted by Edo offered a highly dynamic solution: the moat, which began at the inner citadel, was dug outwards without closing the circle. This allowed for the seamless expansion of the defense line and residential areas without interfering with existing urban functions.

In fact, Edo's urban area organically expanded from the initial Chiyoda and Chuo ward areas to the outer periphery over time. It was this flexible structure that allowed the city to maintain its urban functions while still maintaining Hirokoji and firebreaks after the Great Fire of Meireki (1657). This was an extremely sophisticated system, similar to the "agile" expansion of modern software development.

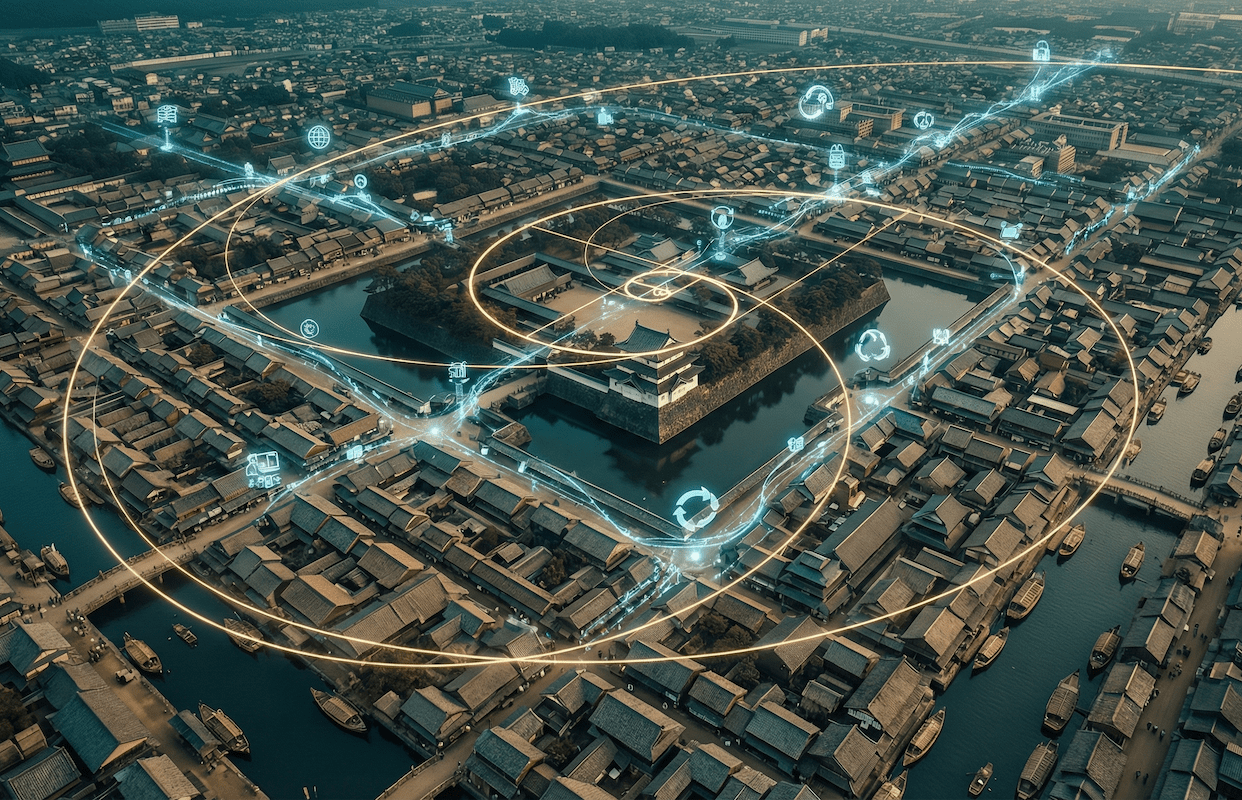

[Map] Edo Castle (currently the Imperial Palace), the starting point of the spiral

The size of Edo compared to other major cities

How large was Edo's growth due to this highly scalable system? Comparing population data for major cities around the world in the 18th century reveals its remarkable scale.

The graph below shows the estimated population in the mid-18th century.

Comparison of populations of major cities around the world in the mid-18th century

Source: Comparative data based on historical demographic projections

As shown in the diagram above, Edo was the world's largest megacity in both name and reality, far surpassing London on the eve of the Industrial Revolution and Paris just before the French Revolution. Of this one million people, approximately 500,000 townspeople, excluding samurai, lived densely in an extremely small area of just 20% (townspeople's land) of Edo's total area.

Normally, such overcrowding would lead to infrastructure breakdowns, food shortages, and the spread of infectious diseases due to filth, causing the city to collapse. However, Edo did not collapse. On the contrary, it continued to function as a clean and safe city.

What made this miracle possible was the "dual use of logistics and defense," which will be explained in the next chapter.

2. The Ambiguity of Infrastructure: The Fusion of Defense and Logistics

The most ingenious aspect of Edo city planning was its "multi-functionality," which allowed a single piece of infrastructure to have multiple functions. In particular, the use of waterways (moats and rivers) was so rational that it would impress even modern city planners.

labyrinthine defense depth

The spiral outer moat, measuring approximately 14 to 16 km in length, was a cruel device that constantly exposed the castle's flank to enemy forces.

Even if the enemy tried to advance in a straight line, they would be blocked by the complex, curved waterways. If they tried to cross the river and reach the bridge (bottleneck), they would be met by concentrated artillery fire from the defenders. In other words, the river functioned as a "labyrinth" that blocked direct lines of sight and fire, forcing the attackers into unfavorable terrain at all times.

The city's main artery

As the era of peace (Pax Tokugawa) took hold, this military barrier was transformed into a major artery that fed the stomachs of the megalopolis.

At the time, land routes were unpaved and transportation costs were high, but water transport made it possible to transport large quantities of goods cheaply. Rice, miso, soy sauce, timber, charcoal, firewood... Nearly all of the heavy goods necessary for daily life were delivered via this spiral canal to riverbanks in every corner of the city.

Logistics network as an "aqua city"

In the city of Edo, waterways were equivalent to modern-day "highways," while land routes were equivalent to "general roads." Traffic flowed from the Tone River system via the Edo River and artificial canals such as the Onagi River to the Sumida River. From there, goods were transported to consumers through canals that ran like blood vessels.

The areas around Nihonbashi in Chuo Ward and the Onagigawa River area in Koto Ward can be considered the centers of this water transport system. Until it was reclaimed during the period of rapid economic growth in the Showa era, Tokyo was literally a "city of water."

[Map] The confluence of the Onagi River and Sumida River, which were major logistics arteries

Another thing worth mentioning is the establishment of resource circulation (circular economy).

In London and Paris at the time, human waste was dumped on the streets, causing serious social problems such as water pollution and infectious diseases like cholera. However, in Edo, the sewage generated in the city was transported by ship to nearby farming villages (Kasai, Gyotoku, Kawagoe, etc.) as valuable fertilizer (night soil), and the vegetables produced there were then transported back to Edo by ship, creating a complete recycling loop.

The canals, dug for defense, supported logistics and even ensured environmental sanitation. This system, which killed three birds with one stone, was what made Edo a sustainable city.

3. Recommendations for Toyako Town: Implementation of the Neo-Edo Model

Deciphering the terrain and updating the "urban operating system"

Now, based on the historical analysis we have done so far, let's connect our thinking to the contemporary urban development of Toyako Town, Hokkaido.

Toyako Town is a municipality with an overwhelming "center of nature" in the form of a huge caldera lake. This topographical feature is structurally similar to Edo Castle (the center of the void) in Edo. However, the current urban structure is limited to a collection of circular roads (lines) around the lake and scattered tourist and agricultural areas (points), and it must be said that organic cooperation is weak.

With a budget of approximately 8 billion yen (general account), of which over 1 billion yen is spent on social security, it is not realistic to wait for large-scale investment from outside. Therefore, I would like to propose reconstructing the Edo system philosophy with modern technology."Neo-Edo model"is.

[Map] The entire Toyako town area where the proposal is based

Specific measures: Creating a spiral cycle

Specifically, we propose a "spiral transformation" in the following three areas. This is not just about building roads, but an attempt to synchronize the flow of people and money.

| Measure area | [Current issues] Division and one-way traffic |

[Neo-Edo Proposal] Circulation and multifunctionality |

|---|---|---|

| Traffic flow planning |

- Concentration on the lakeside road (loop line). -Tourists will not flock to inland agricultural areas. - Evacuation routes in the event of a disaster are limited. |

The spiraling of the "Scenic Highway" A spiral route will be developed to lead people from the lakeside to the inland agricultural area and up to higher ground. It will function as a cycling road in normal times and as an evacuation route to higher ground in emergencies (dual use for disaster prevention and tourism). |

| Water resource utilization |

- Use of the landscape as something to be "seen." -Only some sightseeing boats will be used. -Increased snow removal costs by land. |

Water Mobility & Energy To reduce the cost of maintaining land routes, water transport between the two shores was converted into public transport (modern-day boar-tooth boats). In addition, a district heating system was introduced that utilizes the temperature difference energy of the lake water. |

| economic cycle |

-Tourism spending is flowing out of the region. - General financial resources are being strained due to rising social security costs. -Lack of coordination between tourism and agriculture. |

"Reiwa Land Survey" System By linking tourism demand (hotels and food and beverages) with agricultural production data, we aim to maximize the rate of local production for local consumption. We also have a system that directly recycles hot spring and accommodation taxes into infrastructure maintenance (modern construction). |

Particularly important is the perspective of "hybrid infrastructure for disaster prevention and tourism."

Just as Edo's "hirokoji" and "dotted banks" were places for people to relax in peacetime and also functioned as firebreaks and evacuation sites in times of emergency, Toyako Town should also be designed to serve as a "spiral promenade with spectacular views" that can serve as a "life-saving evacuation route to higher ground" in the event of an eruption of Mount Usu or flooding.

Budgetary measures solely for "preparing for a future disaster" are difficult to maintain in today's financially strained world. However, if "infrastructure that can be used every day and generates income" can "save lives in an emergency," then its maintenance costs can be justified as an investment. This is the ultimate resilience we should learn from the Edo period.

Conclusion: Time to rewrite the city's "operating system"

The greatest lesson to be learned from Edo's "no"-shaped structure is to view a city not as a fixed, physical "box," but as a "living organism" that is constantly metabolizing.

Defense, logistics, sanitation, and the economy. Rather than dealing with these issues individually as vertical administrative tasks, the Edo period's wisdom was to integrate and solve them within a single spiral structure. This is a ray of hope for modern Japan, which is facing an "age of decline" due to population decline and aging infrastructure.

Toyako Town, which has to support welfare and infrastructure with a budget of approximately 8 billion yen, can no longer continue to pursue the Western model of "expansion and consumption." What it should aim for is a return to the Edo model of "recycling and symbiosis," or rather, an update using the latest technology.

Making use of water and circulating it without going against the natural topography. Now is the time to rewrite the city's operating system and begin to paint a spiral towards a sustainable future.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Water circulation and urban development – Examples of urban design utilizing water systems

- Toyako Town: Second Toyako Town Urban Planning Master Plan – Land Use Concept for 2045

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government Bureau of Construction: Edo Rivers and Tokyo Rivers – Historical Changes and Modern Roles

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.