〜What value does this urban structure, which symbolizes national prestige, and the "vastness of the sky" created by strict height restrictions bring to modern cities?〜

*This article is based on information as of January 2026.

"A city is a great book that tells us what a country values most."

Washington DC is the capital of the United States, the most powerful nation in the world. When visiting this city and standing on the banks of the Potomac River, many Japanese people feel a certain sense of incongruity, yet are also deeply impressed. This is because there are no skyscrapers, the symbols of capitalism, like those in Manhattan in New York or Chicago.

A vast, unobstructed view of the sky. A group of stately neoclassical buildings lined up in an orderly fashion. And tree-lined avenues stretching out to the horizon with geometric beauty. These are by no means the result of accidental formation in history. They are the crystallization of an extremely strong "national will" envisioned by a single genius engineer in the wilderness of America, shortly after the founding of the country, at the end of the 18th century.

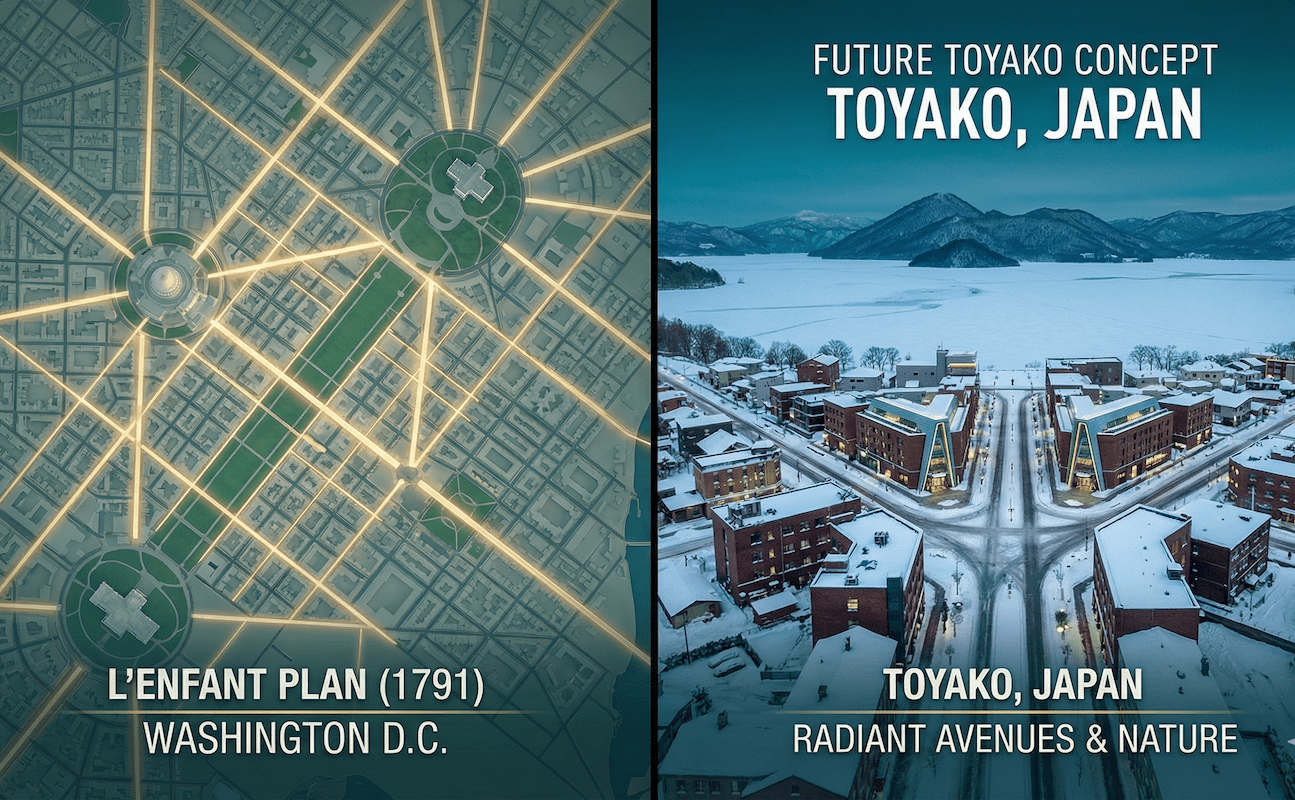

The man in question was Pierre Charles L'Enfant. The grand design he drew up, commonly known as the "L'Enfant Plan," was an incredibly ambitious and grandiose attempt that went beyond mere transportation convenience and efficient land use, attempting to establish the abstract ideal of democracy as a physical spatial structure on the ground.

This article explores in detail how Washington DC came to achieve its "dignity as a capital city," examining its historical transitions and the mechanisms of its urban structure. Furthermore, Hokkaido cities, particularly Sapporo and Toyako Town, which also have origins as "planned cities" and feature grid-like streetscapes, explore what they can learn from the DC model and apply it to their urban development over the next 100 years. From multiple perspectives, we delve into the possibilities and future implications.

1. The Entire Story of the L'Enfant Plan: The Fusion of Baroque and Democracy

A national dream painted on the marshes of 1791

The year was 1791. The United States, which had just emerged from the Revolutionary War, chose the swamps along the Potomac River as the site for its new capital. George Washington, the first president of the United States, entrusted the planning of this undeveloped land to Pierre Charles L'Enfant, a French military engineer and architect.

L'Enfant spent his childhood in Versailles, France, and was greatly influenced by the magnificent gardens of the Palace of Versailles, designed by André Le Nôtre, and the radial urban structure of Paris. He had in mind the aesthetics of "Baroque urban planning," which was prevalent in Europe at the time. However, rather than simply imitating it, he attempted to reinterpret it to fit the ideals of the new American republic.

The standard urban planning at the time was based on a practical "orthogonal grid" that divided the land equally. Philadelphia is a typical example. However, L'Enfant made a bold move. He selected the "Legislative Capitol" and the "Executive" as the two main focal points of the city, and made it the core of his plan to physically and visually connect them."Vast Diagonal Avenues"The two were layered together.

[Three components of the L'Enfant Plan]

-

1. Orthogonal System

The infrastructure for daily life and distribution that forms the foundation of a city. Streets running north to south are numbered (1st, 2nd, etc.), and streets running east to west are given letters (A St, B St, etc.), making it a practical system that makes it easy to identify addresses. -

2. Radiating Avenues

Superimposed on a grid are boulevards that connect major locations via the shortest distances. They are named after states such as Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, symbolizing the unity of the federal system. They function as visual corridors (Vistas) that draw attention to the center from anywhere in the city. -

3. Monuments & Focal Points

Circles and parks are located at the intersections of diagonal streets, and statues and monuments of heroes are placed there to give a strong sense of order and story to the urban space.

This multi-layered structure allows residents to look up at the Capitol and the White House, symbols of the nation, diagonally across the street, no matter where they are in the city. This was more than just a road plan; it was a grand "theatrical installation" designed to imprint the authority and ideals of the emerging American nation on residents' everyday visual experience.

L'Enfant himself was dismissed after just one year due to budget overruns and conflicts with landowners, but the framework of his vision was preserved by his successors, who in turn continued to use it until it was shaped into the Washington, D.C. of today through the 1902 McMillan Plan, established by the Senate Parks Commission in 1901.

Current downtown Washington, DC (around the National Mall)

*You can zoom in and out on the map to see where the grid and diagonal streets intersect.

2. The decision to protect the "vastness of the sky": The bold decision to impose height restrictions

The pride of the capital city that rejected skyscrapers

Another, and perhaps most important, factor determining the landscape of Washington, D.C., is the existence of laws that strictly limit the height of buildings. At the end of the 19th century, high-rise building technology using steel frames was established in Chicago and New York, and cities began to rapidly expand vertically, ushering in the era of the so-called "skyscraper."

However, the Congress and citizens of Washington, DC, staunchly resisted this trend. In 1894, when the approximately 50-meter-tall apartment building "The Cairo" was built, criticism erupted that it would "spoil the cityscape" and "make firefighting difficult." This prompted Congress to pass the following bills in 1899 and 1910:"Height of Buildings Act"was enacted.

What is particularly noteworthy about this law is that it adopts extremely rational and human-centered rules, determining the height of a building not just as an absolute value (for example, a uniform 100 meters), but also based on the "width of the road in front of it."

Detailed Mechanism of the 1910 Act

Let's take a look at the specific calculations that control city skylines.

Buildings in commercial areas are required to be built at least as wide as the road in front of them.Plus 20 feetIt can be built to a height of

*Only a portion of the north side of Pennsylvania Avenue is permitted as an exception, with a height of up to 160 feet (approximately 48.8 m).

Buildings in residential areas areSame height as the width of the front roadYou can only build up to

*This ensures a sunny living environment without any feeling of oppression.

There is a common urban legend that says, "No building can be built taller than the Capitol Building," but there is no legal provision to that effect. However, it is true that the Capitol Dome remains the highest point in the city.

These regulations ensure that the streets of Washington, DC, are always bathed in sunlight, have a breeze, and feel like open skies. This bold decision made over 100 years ago to prioritize public value (landscape and environment) over economic profit (maximizing floor space) underpins DC's unparalleled brand value today.

3. A Thorough Comparison: Washington DC and Sapporo

DNA and turning points as a planned city

Let's now shift our focus to Japan. Sapporo, the central city of Hokkaido in the northern part of Japan, also has its origins as a "planned city," similar to Washington, D.C., which was drawn out of a bare field with a ruler.

In 1869 (Meiji 2), pioneer judge Yoshitake Shima formulated the city plan for Sapporo by combining Kyoto's grid system with an American-style grid based on advice from an American advisory group (including Horace Capron) who had been invited to the city at the time. While the two cities share the common DNA of the "grid," they would follow fundamentally different paths in their subsequent development.

| Comparison items | Washington, D.C. (The Capital of Democracy) |

Sapporo City (The Frontier City) |

|---|---|---|

| The origins of the city | 1791 L'Enfant Plan French Baroque influence |

1869 Plan by the Hokkaido Development Commission Introducing the American-style utility grid |

| Basic structure | Grid + Radial Diagonal Streets Emphasis on symbolism and eye guidance |

Pure Cartesian Grid Emphasis on land use efficiency and snow removal space |

| Central axis (green space) | National Mall Width: approx. 122m x Length: approx. 3.0km A monumental space as a "national garden" |

Odori Park Width: approx. 105m x Length: approx. 1.5km Initially functioned as a fire prevention line |

| Skyline | Absolute height limit Low-rise, homogeneous streetscape of about 40m The sky is wide and open |

Allowing for high-rise buildings Landmarks such as JR Tower (173m) Vertical accumulation due to economic development |

| Urban Philosophy | Authority, Symbolism, and Permanence Choosing to "freeze" the historic landscape |

Development, efficiency, and scalability Choosing "growth" based on economic rationality |

*The table can be scrolled left and right.

Comparative reference: Around Odori Park in Sapporo

*The pure grid structure and the green belt (Odori Park) that runs through the center are clearly visible.

4. Modern Assessment of the L'Enfant Plan: Light and Shadow

The L'Enfant Plan undoubtedly created one of the most beautiful capital cities in the world. However, from the perspective of modern urban engineering, its evaluation is not always positive. We will summarize the "pros and cons" of the DC model, revealed by its operational track record of over 100 years.

■ Vistas

The structure, wherever you are in the city, allows you to see the Capitol and the monuments at the end of the street, creating a strong sense of place. This is an unforgettable experience for tourists and contributes greatly to the city's branding.

■ Human scale and walkability

The low-rise streets offer a relaxed atmosphere and open skyline, making them extremely comfortable for pedestrians. Even in the context of New Urbanism, DC's walkability is being reevaluated, enhancing its appeal as a desirable place to live.

■ One of the highest rent increases in the United States

Economically, height restrictions are a "supply restriction." Because offices and housing cannot be built higher to meet strong demand, rents are skyrocketing. This is a factor that accelerates the exclusion of low-income earners (gentrification).

■ Star Intersections

Where the grid and diagonal streets intersect, six-way and eight-way intersections appear (such as Dupont Circle). These are unsuitable for modern automobile traffic, and have structural flaws that make them prone to congestion and accidents, with long signal cycles.

The impact of height restrictions as seen in data

The graph below conceptually shows the correlation between office rents and average building height in major cities, highlighting just how unique DC is.

[By city: Comparison of building height and rent]

NY (Manhattan)

Super high-rise / high rent

Sapporo

Medium to high rise/Standard

Washington, D.C.

low rise / Ultra-high rent

*Due to supply restrictions in DCs, rents tend to be disproportionately high compared to the height of the building.

5. Implications for Toyako Town, Hokkaido: Strategies to transform landscapes into "resources"

How to present a "natural monument"

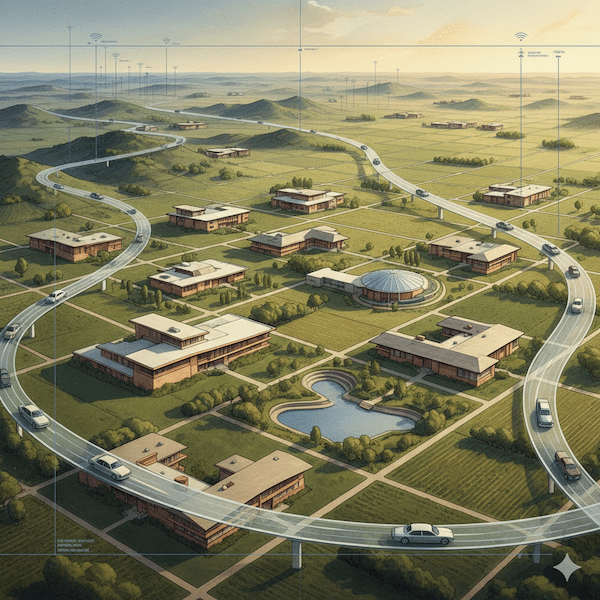

Based on the analysis so far, what can Hokkaido's tourist destinations, especially resort areas like Toyako Town, learn from the DC model?

While Washington DC designed its city to protect its man-made monuments (the Capitol and other monuments), Hokkaido's goal is to protect its sights."Natural Monuments"Mount Yotei, Mount Usu, Nakajima Island, and the beautiful lake surface are the "capitol" of Hokkaido, landmarks of absolute value.

Target area: Toyako Town, Hokkaido (Toyako Onsen Town)

Three specific recommendations

We propose a concrete approach to applying DC's urban planning philosophy to modern Hokkaido.

1. Strict legislation on vistas (view axes)

Designate lines of sight from major streets and squares to Mount Yotei and the lake as "sacred areas." Just as Pennsylvania Avenue in DC guarantees views to the Capitol, construction that blocks views from certain points will be strictly regulated through height restrictions and setbacks (wall setbacks). While this will restrict development in the short term, it will undoubtedly increase the property value (premium) of the entire area in the long term.

2. Commercializing and improving the quality of "the vastness of the sky"

We must avoid the disorderly proliferation of tower hotels seen in some areas such as Niseko. DC has proven that even low-rise buildings can become globally branded cities. By keeping building heights down and instead investing in the quality of design, materials, and street trees, we can establish prestige as a "resort that is comfortable to walk around in."

3. Turning the lakeside into a "National Mall"

We will redefine Lake Toya's lakeside promenade as not just a walking path, but as a "stage for culture and interaction" like the National Mall in D.C. By organically combining geopark elements that convey the memory of the eruption, a sculpture park, and a plaza where markets and events can be held, we will create a "public living space" where tourists and local residents can interact.

Conclusion: Investing in "dignity" beyond inconvenience benefits

Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, once said:

"Cities are the seedbeds of culture"

The example of Washington, DC, teaches us the power of determination to uphold aesthetics even at the expense of efficiency. Diagonal streets made navigation difficult, and height restrictions caused rents to soar, resulting in inconveniences. However, the overwhelming dignity and scenic beauty of the capital that these efforts fostered ultimately became irreplaceable national assets that continue to attract people from all over the world.

Hokkaido's cities are facing a declining population and no longer need any further disorderly "quantitative expansion." What is needed is rigorous and strategic "qualitative maturity" that maximizes the existing rich natural assets (mountains, lakes, and skies).

What kind of landscape will we leave behind for people 100 years from now? The line drawn by L'Enfant 200 years ago quietly but powerfully asks us today to "design for eternal value rather than immediate profit."

Related Links

- National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) – Comprehensive Plan

- National Park Service – The L'Enfant and McMillan Plans

- Hokkaido Construction Department – Promotion of Landscape Formation

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.