〜A new definition of "infrastructure" and a sustainable urban model〜

*This article is based on statistical data and historical materials as of January 2026.

When we delve deeply into the history of urban planning, it becomes clear that there has always been one compelling theme at its core: the struggle against death.

Today, we take for granted the benefits of water and sewage systems, paved roads, and the protection of our living environment through zoning. These were not simply facilities for convenience. They were highly political "governance technologies" invented by the state to physically protect the lives of its citizens and preserve the labor force necessary for industry.

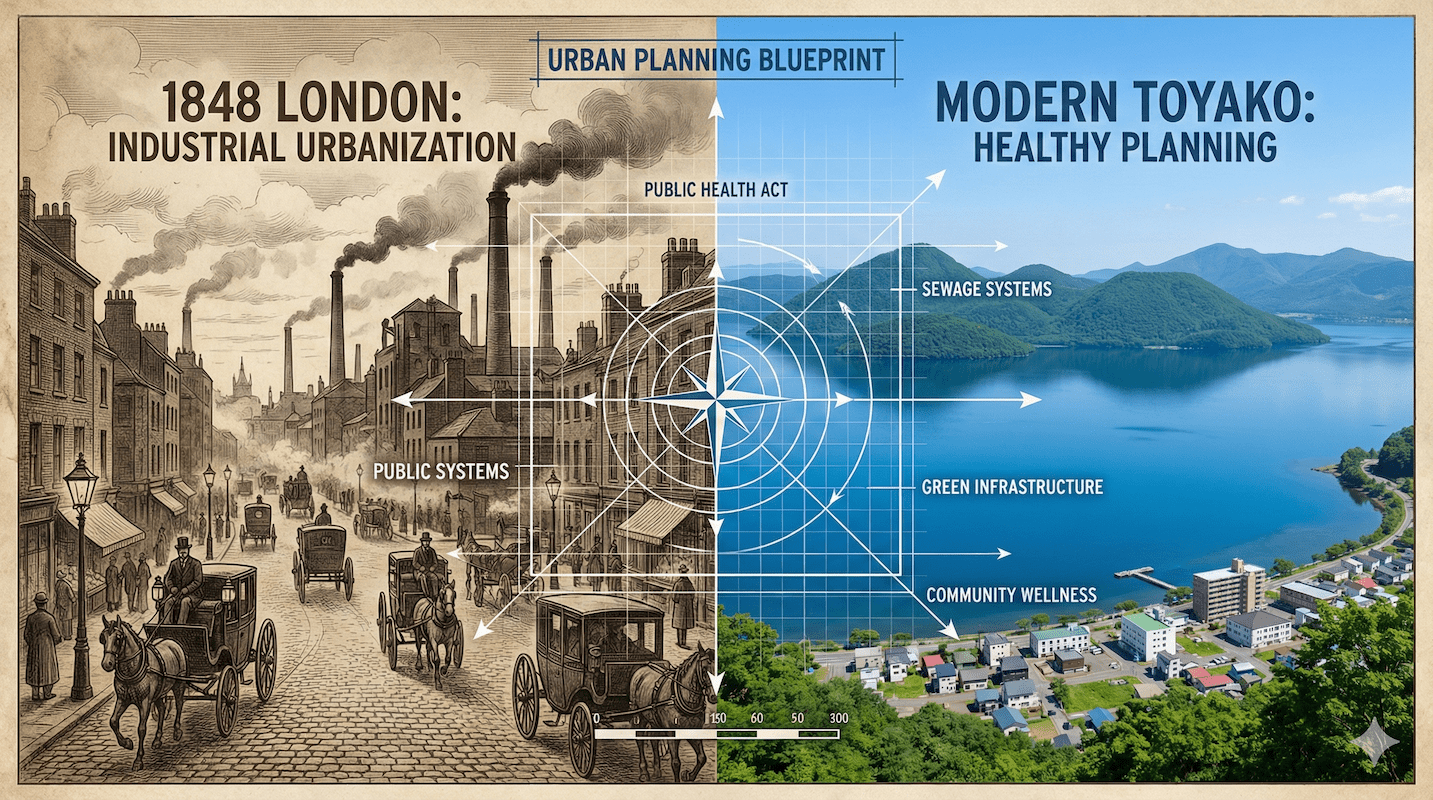

Its origin is recorded in the history of urban planning as the establishment of the City of London in 1848 in the United Kingdom.“Public Health Act 1848”This law, which was created as a prescription for the disorderly urbanization, rampant disease, and poverty that the Industrial Revolution brought about, established the prototype of modern urban planning, which aims to sustain the social system (software) by changing the physical structure (hardware) of cities.

Now, about 180 years later, let's move the setting to a regional city in Japan, specifically Toyako Town in Hokkaido.

Here too, a structural crisis is unfolding that is different from that of the 19th century, but is essentially just as serious. The fight against filth and disease has now morphed into a fight against population decline and lifestyle-related diseases.

This paper projects the cold-hearted logic of 1848 that transformed London into a contemporary local context, and thoroughly discusses the possibilities for how to reconstruct "public health urban development" in Hokkaido, an era of population decline.

1. The Battle Against "Smell": The Dawn of Modern Urban Planning and the 1848 Act

The shadow of the Industrial Revolution and the merits and demerits of the "miasma theory"

Let's turn the clock back to early 19th century Britain. At the time, London was the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution, attracting wealth and people from all over the world, but the urban environment was a hellish one. Workers flocked from rural areas to major cities like Manchester, Leeds, and London in search of work, but the urban infrastructure was virtually nonexistent to accommodate this sudden influx of people.

The lack of a sewer system meant that excrement overflowed into the streets, turning the River Thames into a giant sewer. The overcrowded slums, with poor ventilation, created a breeding ground for deadly infectious diseases like cholera and typhus. Repeated cholera epidemics in 1831 and 1848 claimed tens of thousands of lives across Britain.

The paradigm that dominated the medical world at the time was"Miasma Theory"This was the idea that disease was transmitted through the air by the "bad odor (miasma)" that emanated from decaying organic matter. Although the scientific basis was different from the later germ theory, it ultimately pointed in the right direction in terms of the engineering approach that "removing bad odors = cleaning and drainage" would prevent disease.

In other words, removing the stench of death that permeates cities was the first and greatest mission imposed on the technology known as urban planning.

Edwin Chadwick's cold calculations

There was one man who approached this tragedy not through humanitarian sentiment, but through the cold, sensible analysis of statistics and economics: Edwin Chadwick, a Benthamite utilitarian and social reformer.

He laid the intellectual foundations of public health law with his landmark 1842 report, "Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain." His arguments remain surprisingly modern and rational even today.

Chadwick argued that "unsanitary conditions caused workers to die early or become ill, which in turn plunged their surviving families into poverty. As a result, the burden of poor taxes (welfare costs at the time) increased, putting a strain on the national finances."

In other words, he"Investing in public health (civil engineering) is the public policy with the highest ROI (return on investment) because it reduces welfare costs in the long run."This logic justified huge projects to artificially construct the city's metabolic functions, such as building drainage systems, removing waste, and installing medical officers.

[Illustration] 1848 vs. 2026: Structural changes in the "costs" cities face

(London)

(local city)

*Conceptual diagram: The figures are examples showing relative weights and are not actual statistics.

The "governance mechanism" established by the Public Health Act

The 1848 Act did more than simply order the construction of sewers. Importantly, it invented the "governance" to carry it out.

The General Board of Health was established at the center, and Local Boards of Health were organized in the regions. Of particular note was the conditions for intervention in the regions. This lawA certain mortality rate (e.g., a 7-year average of more than 23 deaths per 1,000 population)or,Ratepayer petition (at least 10%)The central General Board established a framework for the establishment of local boards, subject to the following conditions:

The central government intervened in local government based on objective data (KPI) such as the number of deaths. This was a groundbreaking system that could be considered the beginning of evidence-based policy (EBPM).

2. Modern "miasma": Structural challenges facing Toyako Town

The silent crisis of population decline

Now, let's shift our perspective to present-day Toyako Town, Hokkaido. While London in 1848 faced a dynamic crisis of "explosive population growth and acute infectious diseases," Toyako Town in the 2020s faces a quieter, longer-term crisis of "steadily declining population and chronic social dysfunction."

Toyako Town's population remains at around 8,000, and its aging rate is significantly higher than the national average. What is crucial here is the cold hard fact that the 19th century model established by Chadwick - "debt-repaying infrastructure investment based on the premise of increased tax revenues due to population growth" - no longer holds.

Aging infrastructure and the transformation of assets into liabilities

Toyako Town has a high rate of water and sewerage coverage, with an advanced infrastructure network especially in the Toyako Onsen area, a popular tourist destination. This is a great victory for public health. However, even as the population declines, the length of underground pipes remains the same.

As the number of ratepayers who should support aging infrastructure continues to decrease, maintenance costs will continue to increase in relative terms. Upgrading facilities such as the Tsukiura Water Purification Plant will require a huge amount of money, and as can be seen from documents such as the Toyako Town Waterworks Management Strategy, there are concerns that covering these costs through fee revenue alone will be a future challenge.

Infrastructure, once an "asset" that protected the lives of citizens, is turning into a "liability" that is difficult to maintain. This is the true nature of the "modern miasma" that modern regional cities are facing.

▼ Toyako Town, Hokkaido (Central area)

*While the prefecture has a beautiful lake and hot spring resort, maintaining infrastructure within its vast administrative area is a challenge.

Structural comparison: London 1848 vs. Toyako 2026

We have collated historical facts and contemporary data to summarize the structural differences and commonalities between the two in the table below. Although the time and place may differ, we can see that the essential role of government, which is to "reduce social costs through environmental management," has not changed.

| Comparison items | [London, 1848] Public Health Act |

[Toyako Town in 2026] Healthy town development |

|---|---|---|

| Major Threats |

acute infection (cholera, typhus) Causes: Uncleanliness, poor drainage, overcrowding |

Chronic illness and frailty (lifestyle-related diseases, need for nursing care) Cause: Lack of exercise, isolation, scattered living |

| Intervention target |

Physical environment (underground) Sewers, water pipes, pavement |

Behavior/social environment (ground) Walking trails, exchange hubs, health checkup data |

| Economic logic |

Reduction of the poor tax "When workers die, welfare costs increase." |

Reducing medical and nursing care costs "If the elderly become bedridden, the finances will collapse." |

| Funding Model |

Local taxes (Rates) + central loans Borrowing money secured by future tax revenues from population growth |

Fee revenue + grant tax + regional expansion Reorganization based on the assumption that tax revenues will decrease due to a declining population |

3. Redefining "health": Prospects for a neo-sanitary strategy

Walking is a "modern sewer"

If the answer in the 19th century was to build sewers, what is the answer today?"Walkability (an environment that encourages walking)"This is the construction of.

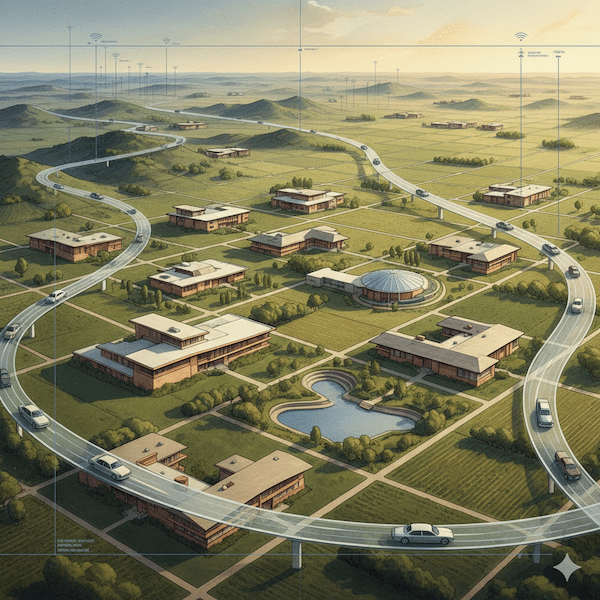

Just as Chadwick once installed underground pipes to quickly drain waste, modern urban planning requires the reorganization of above-ground space to ensure healthy circulation of blood. Toyako Town's goal of becoming a "compact city" in its urban planning master plan is not simply a means of streamlining government administration.

Concentrating medical, commercial, and residential functions in specific locations and creating a structure where people can complete their lives within walking distance (a 15-minute city) is nothing less than the creation of a "preventive medical infrastructure" that naturally (unconsciously) increases the amount of physical activity residents engage in and prevents lifestyle-related diseases. In particular, in Hokkaido, where the amount of physical activity tends to decrease dramatically due to snowfall in winter, prioritizing the development of all-weather walking spaces and well-cleared promenades is a modern-day "sanitation infrastructure investment" comparable to the development of sewer systems in the past.

"Medicalization" of local resources and blue health

Toyako Town has an extremely powerful weapon that London in 1848 did not have: overwhelming natural resources: hot springs and a caldera lake.

Rather than seeing these as merely tourist resources,"Public Health Device for Residents"There is a need for a perspective that redefines it as such.

For example, the effects of hot spring bathing could be scientifically measured and formally incorporated into programs to prevent frailty among the elderly. Alternatively, knowledge on "Blue Health," which has recently attracted attention for its positive effects on mental health, could be utilized to develop the shores of Lake Toya as a "mental infrastructure."

Just as 19th century medical officers "prescribed" clean water, modern urban development can "prescribe" (socially prescribe) a rich natural environment for the health of its residents.

▼ Lake Toya (Blue Health Resources)

4. Data and Consensus Building: Beyond the "Dirty Party"

Allergy to "interference with freedom"

However, such reforms always meet with resistance.

At the time of the 1848 reforms, slum-owning landlords and those who believed in "laissez-faire" (laissez-faire) fiercely attacked the sanitary reforms as an "infringement of individual freedom" and "bureaucratic tyranny." They were derided as the "Dirty Party," but their argument included a fundamental question that is still relevant today: "The government should not interfere in the property and lives of individuals."

Modern "healthy town planning" also faces criticism that it is paternalistic (meddling), and must face head-on the feelings of residents who "don't want to leave the place they are used to living in" that come with consolidation, as well as demands for convenience such as "being able to use cars."

The power of data overcomes emotional arguments

What becomes crucial here is "statistics (data)," Chadwick's greatest weapon.

In promoting reform, "sanitary maps" were used in reports such as the 1842 report (e.g., Leeds), which visualized the correlation between unsanitary areas and mortality rates, helping to persuade opponents.

The same is true in Toyako Town today. Rather than just building "facility that just seems good," they conduct detailed analysis of specific health checkup data and nursing care certification data (KDB) to map "which areas have increasingly serious health issues." They then pinpoint benches and open salons in those areas.

Above all, it shows, in objective figures, how the investment will contribute to reducing future medical and nursing care costs.

Evidence-based dialogue, rather than emotional reasoning, is the only key to moving forward with painful reforms. The integration of water supply businesses through wide-area collaboration will also be impossible without this "rationality based on numbers."

Conclusion: From Clean City to Healthy City.

New Infrastructure Theory for a Mature Society

The historical significance of the London Public Health Act of 1848 lies in its attempt to restore social sustainability by changing the physical structure of the city, which at the time meant protecting the workforce from disease and maintaining the industrial capitalist system.

In contrast, sustainability in Toyako Town in 2026 means maximizing the period of time that residents can live with dignity (healthy lifespan) within a limited population and shrinking financial resources, and preventing the collapse of the local community system itself.

To achieve this, we need the courage to wisely downsize the excessive infrastructure that is a legacy of the era of rapid growth in line with the size of the population, while also redirecting the excess capacity to "wellness infrastructure." This requires wisdom not only to repair old water pipes, but also to transform the roads above them into "roads that people want to walk on."

Just as London pioneered the concept of a "clean city," Toyako Town is now at the forefront of inventing a "healthy city" in an era of declining population. This challenge goes beyond the mere policy of a single local government and has the potential to become a new model for public health and urban planning in Japan's mature society.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Basic Concepts of Urban Planning

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Health Japan 21 (Third Phase)

- Toyako Town: Toyako Town Health Promotion Plan

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.