〜Reconsidering the true value of urban greenery from both the economic and gentrification perspectives〜

*This article is based on information as of December 2025.

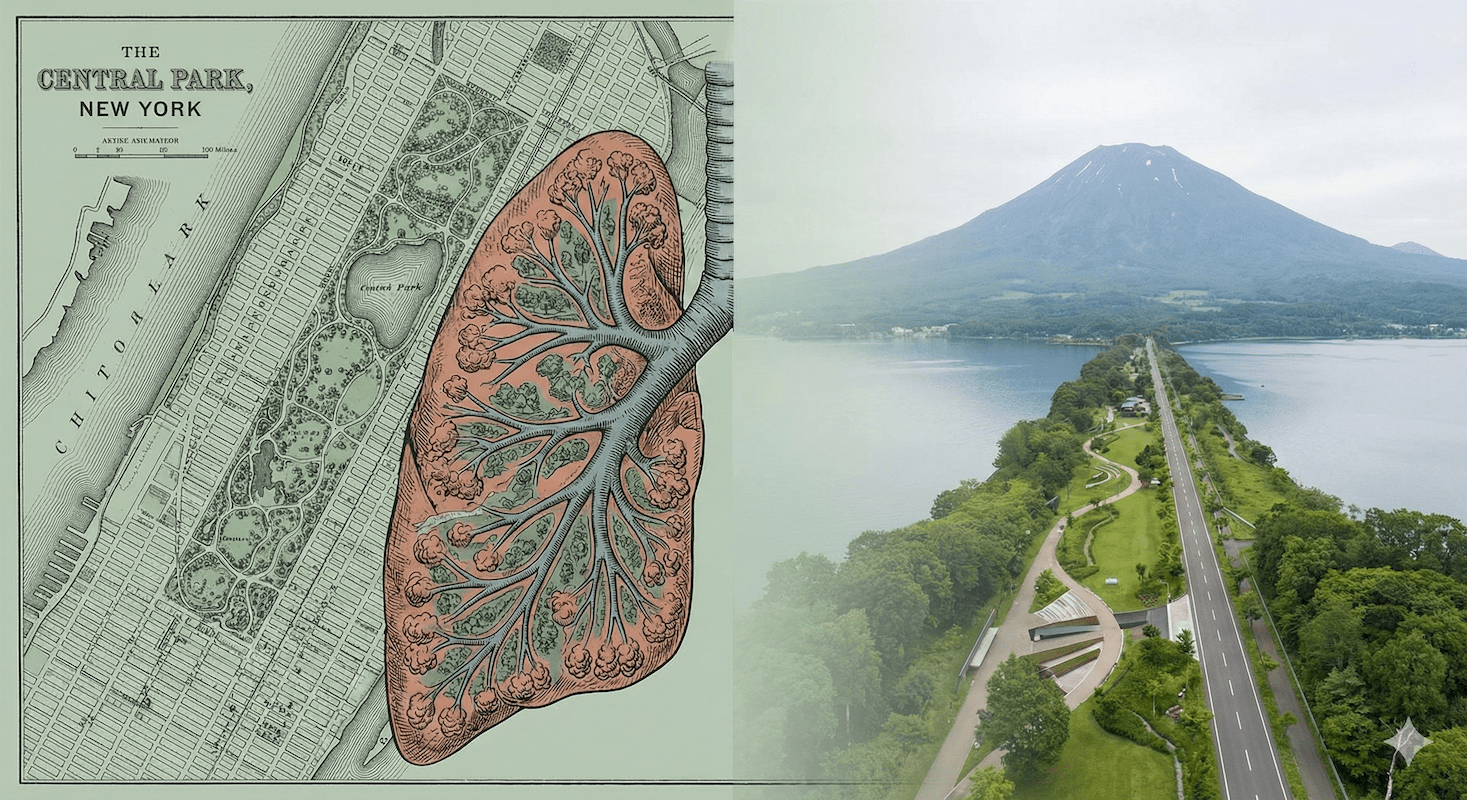

"Giving cities lungs"

This phrase is not merely a poetic metaphor. In the mid-19th century, in New York, shrouded in the soot of the Industrial Revolution, it was a crucial medical and strategic survival requirement for the vast urban organism to avoid suffocation.

The advocate of this idea was Frederick Law Olmsted, the creator of Central Park and known as the father of modern landscape architecture. He defined parks not as a "luxury" for citizens to enjoy in their leisure time, but as "essential infrastructure" that purifies polluted air and relieves mental stress caused by overcrowding.

Now, in the 2020s, as we face new ailments such as climate change, pandemics, and the decline of regional cities, the concept of the "lungs of cities" is becoming more real than ever.

This article will explore the historical origins of Olmsted's ideas, discuss in detail how his DNA was passed on across the ocean to the Hokkaido Development Commission, and how it is being re-implemented in the modern-day urban development of Toyako Town.

1. Background to the invention of the "lungs of the city": The crisis of 19th century New York

The Shadow of the Industrial Revolution and the Battle against the "Miasma Theory"

Let's turn the clock back to the 1850s. Manhattan, New York, at that time was not the glamorous skyscraper city we imagine today. Immigrants from Ireland and Germany flooded the city, causing a population explosion. The sewage system was underdeveloped, the streets were filled with horse manure and garbage, and slaughterhouses and factories were located next to residential areas.

As a result, epidemics of infectious diseases such as cholera, typhus, and yellow fever were frequent, and infant mortality rates were extremely high."Miasma Theory"This was the idea that disease was transmitted by "bad air (miasma)" generated by decaying matter. In the days before bacteriology was established, people believed that the foul odor that filled cities was the cause of death.

Olmsted himself had suffered the tragedy of losing a young child to what was believed to be an epidemic at the time. For him, and for the urban planners of the time, purifying urban air was not a matter of aesthetics, but an urgent sanitary measure to literally "protect the lives of citizens."

Central Park is a "giant air purifier"

The Greensward Plan, won by Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in a design competition in 1858, was a response to this very public health imperative.

They described vast green spaces as the "lungs of the city" and positioned them as public health infrastructure. Trees absorb suspended particles in the air through their millions of leaves, supply oxygen, and lower the temperature. The following discussion of the functions of parks was held within the public health reform movement of the time:

"The air is disinfected by sunlight and purified by trees. The primary purpose of parks is to supply this clean air to the lungs of a sick city."

Furthermore, they placed importance on "mental hygiene." In order to alleviate the mental tension (what we would now call mental health problems) caused by constant commercial activity and overcrowded living environments, they needed a "space of complete immersion" that was completely free from the hustle and bustle of the city.

To achieve this, innovative civil engineering technology was introduced."Sunken Road"The four cross-town traffic transverse roads that cross the park are dug into the ground and screened with vegetation, physically eliminating the "city noise" from the sight and hearing of park users. This allows the park to have a rural landscape of 100%, allowing residents to forget that they are in Manhattan.

▲ Central Park: A huge rectangle stretching 4km from north to south, it is an artificial natural area preserved in the midst of an overcrowded city.

2. Japan-US Comparison: Data on the Resolution of "Parks"

So how should the city's function as a "lung of the city" be evaluated in the modern era? By comparing Central Park, a global success story, with a typical Japanese urban park, we will highlight the structural differences between them.

The overwhelming difference between "investment amount" and "earning power"

The table below compares Central Park with park administration in major cities in Japan. What is noteworthy here is not just the difference in area, but also the "entity of management and operation" and "funding structure."

| Comparison items | new york (Central Park) |

Japan (General urban park model) |

|---|---|---|

| Management entity | NPO (Conservancy) Led by a private nonprofit organization contracted by the government (NYC Parks). |

Government/designated manager Outsourcing management through local government budgetary measures is the norm. |

| Funding structure | Private donations and revenues: approx. 75% They earn a living independently through donations, events, and licensing businesses. |

Taxes and public funds are almost 100% Although the introduction of Park-PFI and other measures is progressing, it is still dependent on taxes. |

| Annual Budget | Approximately 11 billion yen (one park alone) *1This is an exceptional amount of money spent on maintenance of the park. |

Tens of millions to hundreds of millions of yen *Even in large parks, the numbers often differ by one or two digits. |

| Economic effects | Over 210 billion yen per year This includes increased property tax revenue due to rising land prices in the surrounding area. |

Difficult to calculate/limited These effects are often not visualized as macroeconomic effects. |

*On a smartphone, you can scroll the table horizontally to view the results.

*Estimated value based on an exchange rate of 1 dollar = 150 yen. For data, please refer to the Central Park Conservancy Press Kit (2023-2024) etc.

Visualization: Why does the "quality of management" vary?

The biggest difference is the source of the money. Central Park covers the majority of its operating costs through donations from the super-rich and corporations in the neighborhood, as well as businesses within the park. In contrast, many Japanese parks are tax-funded, which means they have a structural weakness in that they are prone to budget cuts due to economic fluctuations or local government financial difficulties.

Below is a simplified graph that illustrates the economic cycle that parks bring about.

[Illustration] Return structure of park investment

* On smartphones, you can scroll the graph horizontally to view it.

In other words, the "cost" of parks (the red bar) is the source of funds that generates a much greater "return" (the green and purple bars) for the city as a whole. Olmsted intuitively understood this mechanism and continued to persuade the City Council that "parks are an investment that will definitely pay for itself."

3. Green gentrification: A side effect of its success

However, the economic success of parks is not necessarily something to be celebrated. One of the most serious dilemmas in 21st century urban planning is"Green Gentrification"is.

By creating a high-quality park (such as the High Line) in a dilapidated industrial area or slum, the area can be transformed. Crime rates drop, trendy cafes and galleries move in, and the city's brand value skyrockets. This is known as the "Central Park Effect."

Specifically, properties within walking distance of a park will be given a "park view premium," and the influx of investment money will strengthen the city's tax revenue base. For the government, this is the very model of successful urban development.

On the other hand, rising land prices and rents hit low-income and minority communities who originally lived in the area hard, forcing them out of their familiar neighborhoods as they find it economically unbearable.

Parks, which were supposed to be created for the sake of public health and equality, end up becoming comfortable gardens for the wealthy and functioning as a mechanism for excluding the socially vulnerable. This paradox is a problem that is quietly unfolding in New York, London, and Tokyo.

The "Just Green Enough" Solution

In response to this issue, recent urban planning studies have"Just Green Enough"This strategy is being proposed. The idea is to curb rapid gentrification by avoiding overly luxurious and touristy park development, and instead limiting the development to green spaces of "moderate quality" that can be used daily by local residents.

How far should we step on the accelerator of development? This sense of balance is what modern park managers are being asked to achieve.

4. Olmsted's DNA is engraved in Hokkaido

Let's shift our perspective from America to Japan, specifically Hokkaido. There is actually a close relationship between Olmsted's ideas and the history of Hokkaido's development.

The Hokkaido Development Commission Advisory Group and Sapporo's "Fire Prevention Line"

In the early Meiji period, the Hokkaido Development Commission invited many experts (hired foreigners) from the United States, including Horace Capron, who designed Sapporo's grid-like streets based on the American Midwest city model.

Located in the center of the city is Odori Park. Originally, this space was not intended as a park, but as a huge open space to prevent the spread of urban fires."Firebreak"However, this functional open space eventually became a place for citizens to relax and evolved into a cultural hub for events such as the Snow Festival.

▲ Odori Park, Sapporo: A "breathing open space" that divides the city into north and south and allows the wind to pass through.

From an Olmsted perspective, Odori Park is the "airway" of the city of Sapporo, functioning as a device to send fresh air to the overcrowded areas in the north and south. The Hokkaido University campus is also officially designated by the university authorities."Lungs of the city"The area is positioned as a cool spot where virgin forests and farms function to mitigate the urban heat island effect.

5. Toyako Town's Challenge: Protecting the Landscape as a "Commons"

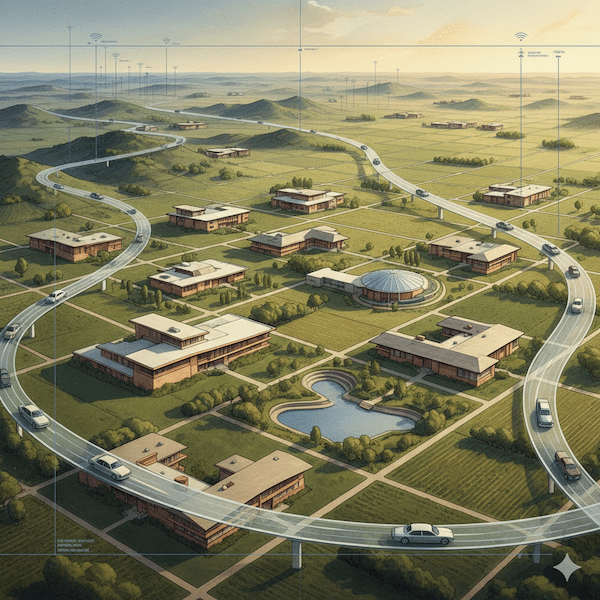

Finally, let's look at the current practice in Toyako Town. For local governments facing declining populations, maintaining parks and landscapes can often be a financial burden. However, Toyako Town is forging a unique path by rethinking the landscape itself as a "source (capital) that generates the economy."

What the "10-meter gap" means

One thing worth noting about Toyako Town's landscape plan is the extremely strict building regulations in the priority sections (designated in the landscape plan) along National Route 230. Let's take a look at the specific numerical standards.

-

① Wall setback (setback) of 10 meters or more

Buildings must be built at least 10 meters from the road boundary. This is an "abnormal" distance, considering that in urban areas, a distance of 1 to 1.5 meters is common. This forces a vast green area (buffer zone) to be created between the road and the building.

-

② Height limit: 10 meters or less

By keeping the building height to the same level as a typical house, around two to three stories, care has been taken to ensure that the view of Mt. Yotei and the outer rim of the volcano (View Corridor) from the road is not obstructed.

▲ Around Lake Toya: To protect the landscape of the national park, strict restrictions are imposed on construction along the road.

What is the purpose of this regulation?"Parkway"A modern reinterpretation of

Rather than simply creating roads for cars, we will create scenic axes that allow movement itself to be a form of recreation. Maximize the value of the "landscape," which is the shared property of the entire region, even if it means partially restricting individual land ownership. This can be said to be the wisdom of a highly advanced form of self-governance that avoids the "tragedy of the commons."

Conclusion: Update the city's "lungs"

The vision that Olmsted presented in Central Park still challenges us 160 years later.

"Is nature in cities a cost (burden) or an investment (asset)?"

The answer is clear: green spaces protect the health of citizens, increase property values, and attract tourists—they are as essential infrastructure for a city's survival as roads and water systems.

And now, new trends are beginning to emerge. Business models surrounding parks are evolving dramatically, with examples such as "Park Rx" (green prescription), in which doctors prescribe walks in parks instead of medicine, and the "OECM (Ocean Ecosystem Management)" certification, which is evaluated in the context of corporate ESG investment.

Regional cities like Toyako have the "strongest lungs" in the form of vast natural surroundings. How we can keep these lungs healthy and allow them to breathe deeply will be the key to determining the prosperity of the next 100 years.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Green Infrastructure Promotion Strategy 2023

- Toyako Town: Landscape Plan and Landscape Ordinance

- Central Park Conservancy: Official Website

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.