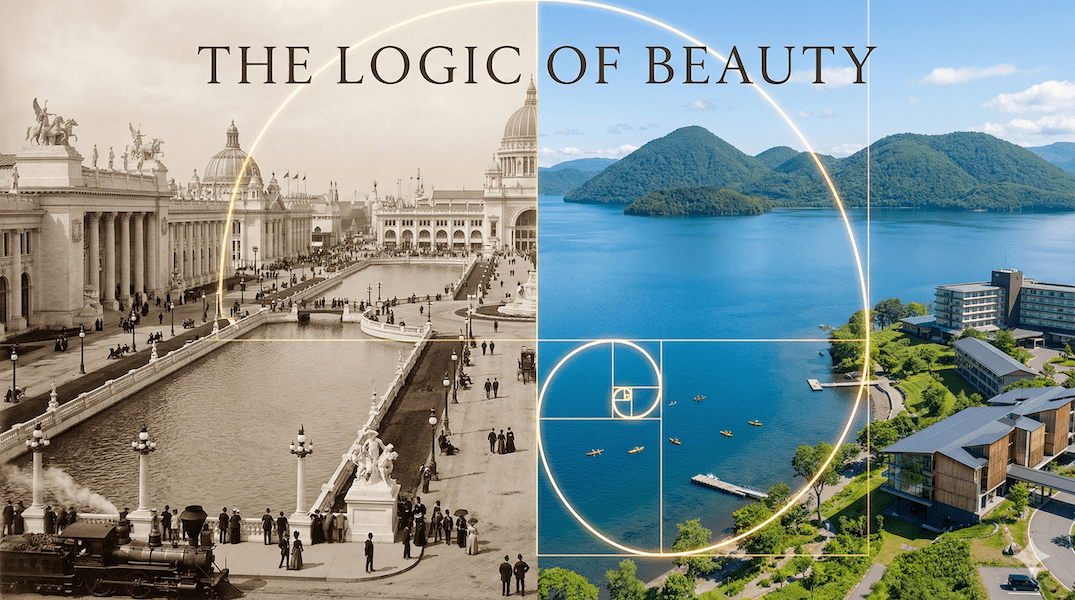

〜The "City Beautiful" movement, which was born at the Chicago World's Fair in the late 19th century, advocated that urban beauty should be the foundation of morality and economics.〜

*This article is based on publicly available information as of January 2026.

What exactly is "aesthetics" in cities? Is it merely "excessive decoration" that is permitted as a result of economic prosperity? Or is it "social infrastructure" that is essential for a city to survive and grow?

In the late 19th century in America, architects proposed a solution to the crisis of cities shrouded in soot and chaos."City Beautiful Movement"This is the idea that planning a city to be beautiful, grand, and orderly is not just for the eyes, but also has the function of encouraging the moral improvement of citizens, restoring social order, and ultimately bringing about sustainable economic development.

Nowadays, this idea is being reevaluated in new terms such as "walkable cities" and "green gentrification." This article delves into the historical and philosophical lineage of urban beauty that spread with the Chicago World's Fair, and examines from multiple perspectives how this spirit has been implemented in Hokkaido, Japan, particularly in Toyako Town, home to a Global Geopark, and how it is generating new "capital."

1. The Origins of the City Beautiful Movement: "White Order" Against Chaos

Chicago, 1893: Utopia emerges in the "black city"

First, let's rewind the clock a little. At the end of the 19th century, America was in the midst of a rapid industrial revolution and urbanization following the Civil War. Chicago, a central city in the Midwest, was experiencing explosive growth as a hub of the railroad network, but this came at the cost of serious urban problems, including air pollution from factory fumes, overcrowding in slums due to a rapid influx of immigrants, and deteriorating sanitation. At the time, Chicago truly resembled a soot-covered "black city."

It was under these circumstances that the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition was held. The site plans presented by architect Daniel Burnham and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted had a powerful visual impact on visitors.

What they created was"White City"It was a model for an ideal city known as the "Ideal City." Its neoclassical architecture, heavily influenced by the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, symmetrical canals and squares, uniform cornice heights, and gleaming white plaster facades, all exuded an overwhelming sense of order, controlled by reason, something that was absent in the chaotic American cities of the time.

Map: Jackson Park, site of the Chicago World's Fair (White City)

It is particularly noteworthy that through this spatial design, Burnham and others expressed a belief close to "environmental determinism." In other words, it was a moral conviction that "if people are placed in a beautiful and orderly urban environment, their spirits will also be noble and the crime and immorality that plague cities will be purged." The success of the Chicago World's Fair sparked the City Beautiful movement, which went beyond being a mere architectural fad and spread throughout the United States as a social reform movement.

| Comparison items | [City Beautiful Movement] (USA / D. Barnum / 1890s~) |

[Garden City Movement] (UK / E. Howard / 1898-) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Approach | Urban remodeling (Reform) Introducing monumental squares and axes to existing urban centers, giving them dignity and order. |

Decentralization Escape from overcrowded cities and build self-sustaining "new cities" in the suburbs that coexist with nature. |

| Design Language | Neoclassical (Beaux-Arts style), geometric straight lines, and magnificent tree-lined boulevards. | Organic curves, vernacular architecture, cottage style, and proximity of work and home. |

| The value we aimed for | Civic pride, social integration, and indoctrination through visual beauty. | Public health, quality of life, and return of property values through land sharing. |

*Both groups shared the same goal of overcoming the ills of modern cities, but their prescriptions (renovating the city center or escaping to the suburbs) were in stark contrast.

2. The Merits and Demerits of Beauty: Jane Jacobs' Condemnation and Modern Reevaluation

The pros and cons of "Don't make small plans"

Barnum is"Make no little plans"These are some of the most famous words in the history of urban planning. He argued that only a logical and grandiose master plan can get people's blood pumping and continue to influence future generations. Based on this idea, the redevelopment of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (the McMillan Plan) and the construction of civic centers (government districts) in San Francisco and Cleveland were carried out one after another, and the profession of "urban planning" was established.

However, in the mid-20th century, this movement came under scathing criticism for being "authoritarian." Now, in the 21st century, ironically, there is an interesting backlash, with its "economic value" being rediscovered.

In 1961, urban journalist Jane Jacobs, in her classic book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, is often quoted as criticizing the City Beautiful movement and its successors as an "architectural design cult."

What she saw as problematic was the consequences of grand plans."Death of the City"In order to prioritize geometric beauty, existing low-income communities were cleared (slum clearance) and functions were strictly separated, resulting in the disappearance of the everyday bustle of people from the streets. For her, true urban beauty was not the geometric patterns seen from above, but the "ballet of the streets" itself, where safety is maintained by the diverse people coming and going and keeping an eye on each other.

On the other hand, the success of The High Line in New York in the 21st century has attracted attention as an example of how investing in aesthetics can produce an extremely high ROI (return on investment).

This project, which transformed an abandoned Manhattan railroad track into an aerial greenway, has seen accelerated real estate development in the area. This can be seen as a modern manifestation of the "City Beautiful," but at the same time, it also presents a new challenge: "green gentrification" (rising land prices and the exclusion of low-income earners due to environmental improvements). While "beauty" can make people happy, it can also function as a device for selection.

Economic effects of "urban beauty" as seen in data and points to note

The economic impact of urban aesthetics is no longer merely subjective. Numerous studies using the hedonic approach (analysis of price-forming factors) suggest that the quality of green spaces and landscapes has a positive impact on land prices. Below is a model of a reported example of land price fluctuations around New York's High Line.

[Figure 1] Changes in surrounding real estate values before and after the opening of the High Line (image)

(Early planning stage)

(Start of construction)

(2nd season opening theme)

*Modeling of reported examples based on data from the NYC Finance Department and other sources (such as an increase of 1,031 TP3T between 2003 and 2011).

However, some academic studies have estimated that the nearest area will see an increase of approximately 35%, so it is important to note that it cannot be concluded that the entire increase is due to the High Line alone.

3. Acceptance and evolution in Japan and Hokkaido

The idea of "wide-area landscape" sprouted in Hokkaido, a pioneering land

Now, let's shift our focus to Japan. Japan's urban planning legislation began with the introduction of Western technology during the Meiji period, but Hokkaido has a unique historical background, having been governed by the Hokkaido Development Commission, and has followed a different path to urban development than Honshu.

For example, in Sapporo and ObihiroGrid-like streets (checkerboard streets) planned during the modern development periodThe wide roads and road widths reflect the strong influence of American urban planning. This fusion of the vast land and Western-style urban structure is the source of Hokkaido's unique scenic beauty.

Furthermore, Hokkaido's landscape administration has taken a unique path. Specifically, this was followed by the "Hokkaido Beautiful Landscape Creation Ordinance" enacted in 2001 (Heisei 13), and then the "Hokkaido Landscape Ordinance" which came into effect in 2008 (Heisei 20) after the Landscape Act was enacted. The following characteristics can be seen in these efforts.

-

① Emphasis on wide area coverage:

The idea was to treat the continuous mountain ranges, roads, and rivers that extend beyond the boundaries of administrative districts (cities, towns, and villages) as a single "wide-area landscape" and to preserve it comprehensively. -

② Shading public works:

Not only did it regulate private development, but it also required that the prefectural government take into consideration the landscape in its public works projects (road construction and river improvement works). The government's stance of "leading by example" was groundbreaking in the vertically divided administrative structure of the time.

4. Case Study: Practicing "Beauty" in Toyako Town

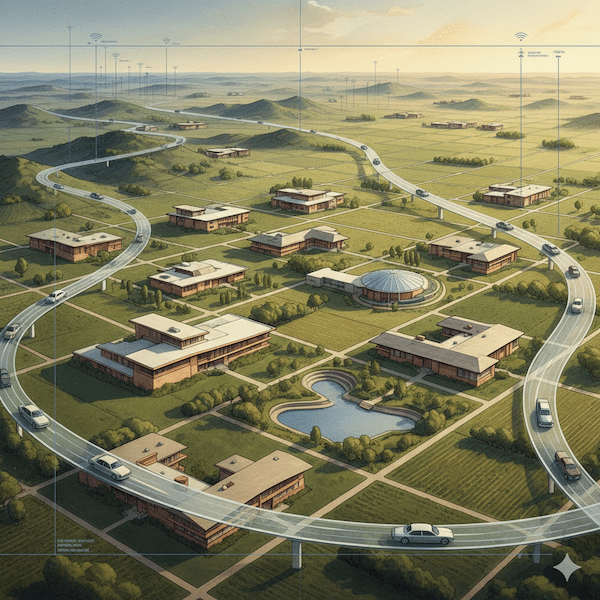

So how are the genes of the City Beautiful movement manifesting themselves in modern Toyako Town, and what kind of economic value is it generating? We will analyze this through the Toyako Town Landscape Ordinance, which came into effect in 2021 (Reiwa 3), and the town's activities as a UNESCO Global Geopark.

Static beauty and dynamic memories

Toyako's landscape strategy has two distinctive features that set it apart from classic "urban beauty."

First,"The aesthetics of disaster ruins"Mount Usu erupted four times in the 20th century. Normally, destroyed roads and buildings are removed as "ugly rubble" and considered an obstacle to reconstruction. However, Toyako Town has chosen to preserve these as a reminder of the "changing earth" and has developed them into walking paths.

This is the polar opposite of the Barnum-esque beauty that aims for orderly harmony, and is a presentation of the "sublime beauty" that arises from the contrast between the threat of nature and human activities. Here, a depth is born as a narrative of the land, not just superficial decoration.

Secondly,"Timeline design"The Toyako Long-Run Fireworks Festival, which takes place every night for more than six months, creates a dynamic landscape using the nighttime lake surface as a canvas. This not only increases the satisfaction of tourists with their stay, but also acts as a powerful lever to attract the economic activity of staying overnight.

Map: Coexistence of destruction and regeneration - Nishiyama foothills crater walking trail

Landscape regulation as an investment in the future

In addition, Hokkaido's resort areas, including Niseko and Lake Toya, are facing increasing pressure for development in anticipation of inbound demand. What is strategically important here is regulatory guidance that "improves quality" rather than simply hindering development.

The Toyako Town Landscape Ordinance strongly requires businesses to harmonize with the surrounding environment (in terms of color, height, and design). At first glance, this may seem like a restriction on economic activity, but in the long term, it helps to avoid the risk of brand damage due to uncontrolled development and maintain the asset value of the entire region.“Capital defense measures”Protecting the beautiful skyline and the right to view the lake goes beyond the short-term profits of individual hotels and directly leads to maximizing the commons of the entire region.

[Figure 2] Sustainability of tourism destination brands brought about by landscape conservation

(Sustainable growth)

(The decline after the boom)

■Red line:A "tragedy of the commons" pattern in which short-term development priorities lead to deterioration of the landscape and a reduction in its attractiveness.

■ Blue dotted line:Qualitative control through ordinances and other measures will maintain long-term brand value and repeat customers.

Conclusion: What is the "big plan" for the 21st century?

The 19th century City Beautiful movement sought to change society by bringing "visual order" to cities. While its authoritarian aspects were later criticized, their insight that "the environment affects people and the economy" is being vindicated by modern data.

The practice in Toyako Town is not simply about making buildings beautiful, but about designing a harmonious system that combines the overwhelming natural force of the volcano, the memory of the disaster, and the economic activity of tourism.

Modern "urban beauty" is not just about superficial cosmetics,An "OS (Operating System)" that balances sustainability and economic rationality (ROI)What is required of us is not to be satisfied with "small plans" like Burnham did, but to draw up "designs for grand relationships" that look ahead to the natural environment and human relationships 100 years from now. This will be the greatest asset for cities to survive in Japan's era of population decline.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Landscape town development initiatives and support measures

- Toyako Town Regulations: Toyako Town Landscape Ordinance

- City Planning Institute of Japan: Historical Development of Urban Planning

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.