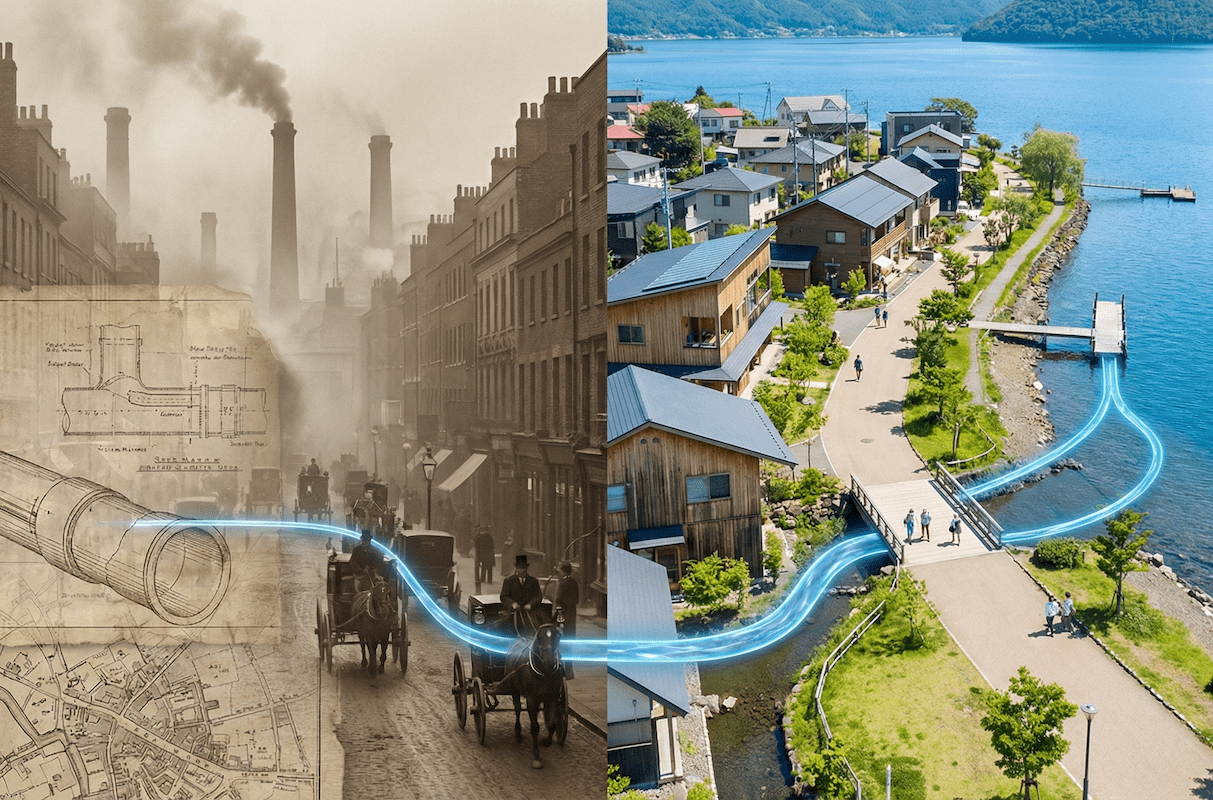

〜Evolution from "survival" to "well-being" through urban development and infrastructure maintenance〜

*This article is based on publicly available information and historical documents as of January 2026.

*External content such as maps may be displayed differently depending on the device environment.

In modern Japan, we take for granted the urban functions of "turning on the tap will produce clean water" and "sewage will flow outside the home and be treated." However, these did not arise spontaneously. They were won after bloody debates in the 19th century, through a dramatic transformation of the social system that was called a "revolution" in human history.

The story takes place in the mid-19th century, in London, the capital of the British Empire, enveloped in the heat, soot, and unbearable stench of the Industrial Revolution. In this city, one man published a shocking report.Edwin Chadwick。

The "Sanitary Reform" he led was not simply a matter of cleaning up the city or expanding the medical system. It was a ground zero of the modern welfare state and urban planning, proving with cold, hard-nosed statistical data that "it is the physical environment of the city that determines the fate of people and the economy of a nation," and establishing an idea in which the government manages and protects the lives of its citizens through infrastructure development.

This article delves deeply into Chadwick's lonely struggle and the historical background, and unravels the challenges of infrastructure maintenance and urban development facing modern Japan, particularly regional cities such as Toyako Town in Hokkaido, using wisdom from 180 years ago. From public health for survival to urban design for well-being, let's trace the path of this evolution.

1. The Paradox of Pollution and Prosperity: The Reality of 19th-Century London

The "suffocation of cities" that progressed in the shadow of the Industrial Revolution

In the early 19th century, Britain was at the height of its industrial revolution and reigned as the world's economic power. However, behind this glorious prosperity, the urban environment was on the verge of collapse.

At the time, London's population was exploding, and workers from rural areas were crammed into shabby tenements with no ventilation or drainage. There was no sewer system yet, so human waste accumulated in cesspools in the basements of buildings or was dumped directly from windows onto the street.

Furthermore, deadly infectious diseases such as cholera and typhus plunged people into the depths of fear at the time. In particular, the cholera epidemic of 1831-1832 claimed the lives of approximately 32,000 people in the UK and caused panic in society. However, at the time, the "germ theory" as the cause of disease had not yet been established, and it was believed that diseases were transmitted by "foul-smelling, polluted air (miasma)."

Although based on this "incorrect scientific belief (miasma theory)," it was Edwin Chadwick who ultimately came up with the correct solution: "removing the cause of the odor - the filth."

▼[Reference map] London (Soho district, around Broad Street), the scene of the 19th century sanitary reform debate

2. A revolutionary shift in definition: poverty is not a "fate" but an "environment"

From moral issues to engineering physics

In British society up until the 1830s, poverty and illness were widely believed to be "moral shortcomings of the individual" or "the will of God." The dominant view was that people were responsible for their own poverty, that they were poor because they were lazy, and that they were ill because they were unhealthy.

However, Chadwick, a lawyer who was strongly influenced by Jeremy Bentham's utilitarianism (the greatest happiness for the greatest number), came across facts that overturned this common belief during his investigations of the Poor Law Commission. He walked through the slums with investigators and saw firsthand the reality that workers were not "not working (lazy)" but "unable to work (incapacity)" due to illness caused by poor living conditions.

Here, he separated the causes of poverty and disease from individual qualities and redefined them as being due to the unsanitary physical environment of cities (poor drainage, insufficient ventilation, overcrowding). This shift in perception is the essence of public health reform.

That is,"If the cause lies in the physical environment, the solution is not preaching or compassion, but civil engineering and administrative intervention."This established the theory.

3. Statistics as a weapon: Making the disparity in deaths visible

The 1842 Report Reveals the "Price of Life"

In 1842, Chadwick published his Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. Although the report was technically a parliamentary document, the government was hesitant to address its shocking contents, and so it was essentially self-published and widely distributed under Chadwick's name.

What makes this report a historic milestone is that, in addition to its descriptive portrayal of misery, it also used groundbreaking comparative statistics. He used the indicator "Average Age at Death" to expose disparities not only between classes but also between environmentally friendly rural areas and polluted urban areas.

| Class/area of residence | [A] Rutland (Clean rural areas) |

[B] Manchester (industrial cities/slums) |

|---|---|---|

| Professionals and wealthy people | 52 years old | 38 years old |

| Merchants and craftsmen | 41 years old | 20 years old |

| Laborers and workers | 38 years old | 17 years old |

Source: Based on the Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain (1842)

*Average age at death is different from average life expectancy based on life tables.

Data visualization: lost time

*When comparing the average age at death, the wealthy urban population was at the same level as rural workers.

What this data eloquently revealed was not the simple fact that "people die because they are poor." It was the fact that "even rich people will die if they live in a bad place (environment)." Unsanitary urban environments were eroding the lives of not only the poor but also the wealthy.

This "shared fear" was a powerful driving force behind the enactment of the Public Health Act of 1848, justifying massive investments in water and sewerage systems. Chadwick elevated public health from a "charity" to "self-defense."

4. The Light and Dark Side of Reform: Conflict between Administrative Intervention and Freedom

Chadwick's reforms dramatically reduced mortality rates in the long term, but the process was not smooth. He faced enemies even more formidable than bacteria: vested interests and the obsession with freedom.

■ Preserving the workforce and sustaining cities

Chadwick's argument was based on economic rationality. He argued that the death of a worker from illness at a young age meant a loss of the costs of upbringing (education and upbringing) that had gone into it, and led to an increase in the poor tax to support the surviving family.

■ Standardization through centralization

Believing that epidemics could not be prevented through disparate responses from different regions, a top-down approach was adopted in which the central government (Central Health Commission) was given strong authority and forced to develop infrastructure.

■ Resistance to paternalism

The idea of "government entering private homes and forcing them to clean" was intolerable interference for the liberal British of the time, and The Times newspaper at the time vehemently opposed it, writing that "people would rather risk cholera than be bullied into health."

■ Violation of local autonomy

Central orders that ignored local conditions were criticized as "tyranny" and ultimately led to Chadwick's own downfall (1854).

The modern-day "burden-benefit" dilemma

In particular, the issue of who should bear the huge costs of infrastructure construction provoked fierce resistance from landowners and taxpayers, who wondered, "Why should we have to pay high taxes for the sake of the poor?"

However, this issue is very similar to the challenges facing local governments in modern Japan, particularly in Hokkaido. While the infrastructure built during the period of rapid economic growth is reaching the time for renewal, tax and user fee revenues are declining due to a declining population. "Who will bear the cost of maintaining the infrastructure, and to what extent?" This question, raised in London 180 years ago, is now being confronted once again, in an even more serious form, before our very eyes.

5. From "Survival" to "Well-being": Hokkaido's Challenge

The 2025 Problem and Smart Infrastructure Downsizing

In Chadwick's time, the biggest issue was "how to build (construction)," but in modern-day Toyako Town and other regional Japanese cities, the question is "how to maintain or wisely downsize (downsize)."

For example, Toyako Town's "Sewerage Business Management Strategy" focuses on balancing sound management amid a declining population, measures to address the deterioration of facilities built in the reconstruction effort following the 2000 eruption of Mount Usu, and strengthening the infrastructure to take into account future disaster risks. As the population declines, the cost of maintaining infrastructure per person will skyrocket. This "silent crisis" calls for sophisticated political judgment on which functions to retain and which to consolidate.

▼[Reference map] Toyako Town, Hokkaido, where the coexistence of the natural environment and infrastructure maintenance is being questioned

Walkable city planning and the "modern investigator"

In the past, public health was a fight for survival, preventing infectious diseases such as cholera, but today the concept has expanded to include the pursuit of well-being, such as preventing lifestyle-related diseases and social isolation.

Chadwick aimed for a "city free of filth," but now cities in Hokkaido such as Sapporo and Muroran have been designated "walkable cities" by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, and are in the process of reorganizing their spaces from car-centered to people-centered.

Toyako Town is also seeing grassroots activities that echo this trend. For example, the Health Promotion Committee organizes Nordic walking events in January, when snow accumulates. These events encourage residents to take the lead in changing their behavior in response to a health issue specific to the region: lack of exercise during the winter. While Chadwick's surveyors of the past exposed the dire conditions in slums, today's promoters create "opportunities for action" for residents to improve their own health.

| Comparison axis | 19th century: Chadwick type | 21st century: Hokkaido Toyako type |

|---|---|---|

| Main enemy | Cholera, typhus, sewage | Lifestyle-related diseases, isolation, aging |

| Solution (hardware) | Sewer pipe and pump installation | Sidewalk maintenance, plazas, snow removal |

| approach | Forced intervention (Top-down) | Nudge behavioral change |

Conclusion: The courage to face hidden costs

Edwin Chadwick's greatest legacy is not just the physical pipes of sewerage. He believed that investment in urban infrastructure should not be just an engineering project or a money pit, but a way to make the city a better place."Investment in the Future"This has been statistically proven to be the case.

His cold-hearted analysis that "premature death is a loss for the nation" can be rephrased in modern times as "extending healthy life expectancy is the greatest economic measure and the key to revitalizing local communities."

Facing up to "invisible costs" such as aging infrastructure and harsh winter environments, and transforming them into "assets" through the power of technology and community, this battle that began in the slums of 19th-century London has transformed into a challenge to protect our health and future in a beautiful lakeside town in Hokkaido. We now need Chadwick's "eyes to face the facts" and "courage to face change."

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Walkable City Promotion (Creating a comfortable city where people want to walk)

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Current status and issues of water administration

- Toyako Town: Sewerage Business Management Strategy

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.