〜The Ringstrasse: Vienna's miraculous urban transformation in the 19th century〜

*This article is based on literature and statistical data as of January 2026.

There are moments in history that determine the fate of a city.

Approximately 170 years ago, on December 20, 1857, a handwritten letter from Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I to his Minister of the Interior forever changed the very fabric of the city of Vienna. The decree, which begins with the words "It is my will" (Es ist Mein Wille), was the signal to demolish the city's ramparts, which had physically bound it since the Middle Ages, and to free the city into the modern era.

Many of the answers to the challenges facing modern Japan, particularly regional cities like Hokkaido - updating aging infrastructure, lack of tax revenue due to population decline, and responding to changing tourism needs - actually lie hidden in Vienna's 19th century urban redevelopment project, the Ringstrasse (Ring Road).

How did they establish a self-sustaining system called the "Urban Expansion Fund" and create one of the world's best landscapes, despite the country's tight financial situation? And what kind of innovation will their "insightful asset management" and "spatial presentation techniques" bring to the Toyako and Sapporo areas where we live?

This paper goes beyond mere historical commentary to dissect the Vienna case from the strategic perspectives of "maximizing capital" and "designing relationships," and reconstructs it as knowledge that can be applied to modern urban management.

1. The alchemy that transforms "negative legacy" into "wealth"

The stagnation of 19th-century Vienna and the potential of "Grassis"

First, let's clarify the situation Vienna found itself in at the time. Until the mid-19th century, Vienna was a fortress city surrounded by double walls. Inside was the densely populated "inner city" (Innere Stadt) where the imperial court and aristocrats lived, and outside was the "suburbs" (Vorstadt) where workers who had flocked in as a result of the Industrial Revolution lived.

Separating the two was a massive city wall, built to protect against sieges by the Ottoman Empire, and the shooting square known as "Glacis" that stretched out in front of it. With the advent of modern weaponry, these spaces lost their value as defensive structures, and became a "negative legacy" in terms of urban sanitation, with dust flying in the summer and turning into a quagmire in the winter.

However, the emperor and the technocrats of the time saw in this "useless piece of junk" economic potential worth trillions of yen today. The vast state-owned land, measuring approximately 2.4 million square meters (about the size of 51 Tokyo Domes), was located in a prime location in the city center. There was no reason not to use it as a seed site for urban development.

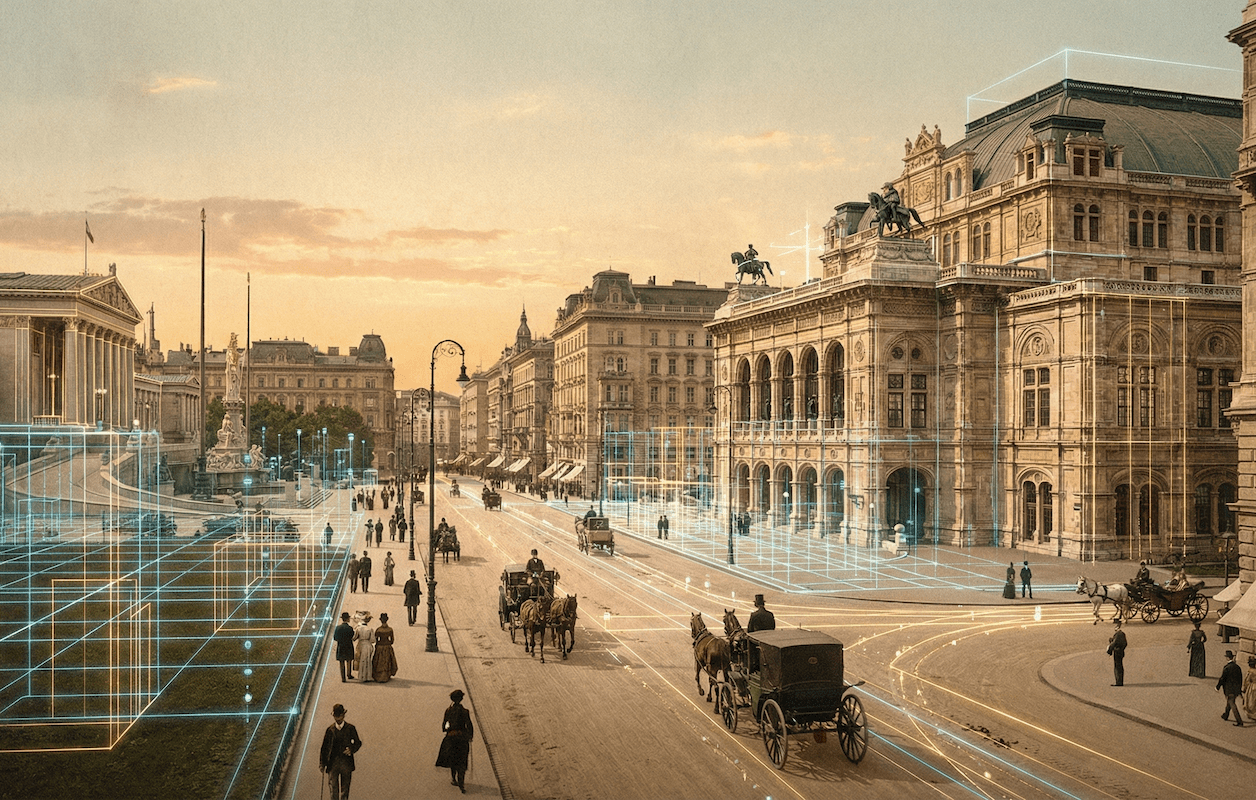

▲ The current Vienna Ringstrasse. You can see the horseshoe-shaped structure that surrounds the old town.

The invention of the "Urban Expansion Fund"

Here, it was introduced"Urban Expansion Fund (Stadterweiterungsfonds)"This was a groundbreaking special accounting scheme, which could be considered a precursor to modern PFI (Private Finance Initiative) and urban regeneration mechanisms.

The system was extremely simple and rational. First, the city walls and glacis were removed, and the resulting land was rezoned. The residential land, excluding the public land for roads and parks, was then sold at a high price to private investors. The profits from these sales were then used to fund the development of road infrastructure and the construction of public buildings such as the National Diet Building, the Opera House, and art museums.

Below is a comparison of the flow of funds under this scheme.

Comparison simulation of funding models

*Since public works costs are covered solely by taxes, budget constraints become a bottleneck.

*Maximize profits from the sale of unnecessary assets (walls) and return the entire amount to public investment.

The development of the Ringstrasse was promoted under a system in which the revenue from the sale of land obtained when the fortifications were demolished was pooled into a fund and recirculated to public buildings, etc. On the other hand, the city of Vienna (municipal government) also had to bear separate burdens such as infrastructure development, so the financial impact was not uniform, but from a national level, there is no doubt that it was an extremely rational capital maximization strategy that transformed the cost center of "military facilities" into the profit center of "real estate."

Incentive design: 30-year tax exemption

However, simply selling land would not have led to such rapid development. The government provided powerful incentives to drive the desire of private capital.

"If construction begins within one year of purchasing the land and is completed within the specified period, property taxes will be exempted for the next 30 years."

This time-limited preferential treatment ignited the competitive spirit of the emerging bourgeoisie and Jewish financiers. To demonstrate their social status, they competed to build magnificent buildings modeled after the palaces of the nobility. In exchange for temporarily giving up tax revenue, the government gained the speed at which the city was completed and the quality of its landscape.

| item | Traditional city management | Vienna Model |

|---|---|---|

| funding source | Collection of taxes from the people | Profit from the sale of state-owned land (unnecessary assets) |

| Developer | Bureaucratic-led public works projects | Public-private partnership through the "Urban Expansion Fund" |

| Motivating the private sector | None in particular (rather subject to regulation) | 30-year tax exemption and branding |

| Deliverables | Minimal infrastructure | A city of world-class art |

2. Ringstrasse as a "theater city"

What makes the Ringstrasse unique is not just its economic scheme: once completed, the urban space itself served as a highly calculated platform for transmitting political and cultural messages.

The buildings along the ring were built in a style known as "Historicism." This was not simply a nostalgic aesthetic, but rather a sophisticated manipulation of symbols that referenced past styles to suit the building's function and expressed an ideal political system and culture.

- ● Greek Revival style (Parliament Building)

Citing Athens, the birthplace of democracy, the poem expresses the desire for parliamentary democracy in a multi-ethnic empire. - ● Neo-Gothic style (City Hall)

With reference to medieval autonomous cities (such as those in Flanders), the work visualizes the autonomy and pride of the Viennese people as they opposed imperial power. - ● Renaissance style (universities and art museums)

Citing an era in which humanism and art flourished, the museum asserts itself as a temple of knowledge and beauty.

However, the plan was not without its critics. The late 19th-century architect Camillo Sitte harshly criticized the Ringstraße, calling it "too broad." He pointed out that it would lose the intimacy of the "enclosed spaces" of medieval squares and make people feel isolated.

Moreover, behind the Ringstrasse's glamorous façade lay the squalid "miitkaserne" (rented barracks), where the rapidly growing working class lived. The fact that the brilliance of the city was inextricably linked to social divisions offers an important lesson when considering modern-day gentrification (changes in residential areas due to the rise of luxury).

In modern urban planning, we tend to think of buildings as simply "functional boxes." However, the example of Vienna teaches us that architecture can also be a "media" that conveys political messages and cultural identity. A city's design code directly expresses the local philosophy.

3. Shift to Lake Toya, Hokkaido: Waterside Ring Concept

So how can we apply this historical knowledge to modern-day Hokkaido, particularly tourist destinations like Toyako Town? Although the scales are different, there are certainly structural similarities between the two, and the possibility of adapting them to other uses.

Comparative Analysis: Vienna and Toyako Geometry

Vienna's Ringstrasse and the Toyako Circular Road may seem unrelated at first glance, but they share a common geometric feature: a circular structure. Making the most of this characteristic shape is the key to the strategy.

| Comparison items | Vienna (Ringstrasse) | Lake Toya (Lakeside Circumferential Road) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall length/scale | Approximately 5.3 km | Approximately 36 km |

| formation origin | Site of removed castle wall (artificial boundary) | Caldera topography (natural boundary) |

| Functional Role | Urban corridors, cultural facilities, and transportation arteries | Tourist tours, national park scenery, residential roads |

| Current Issues | Moving away from the car-centric approach of the past (Large-scale bicycle path construction in 2025) |

Dependence on transit tourism and lack of secondary transportation Separation of hot spring town and natural area |

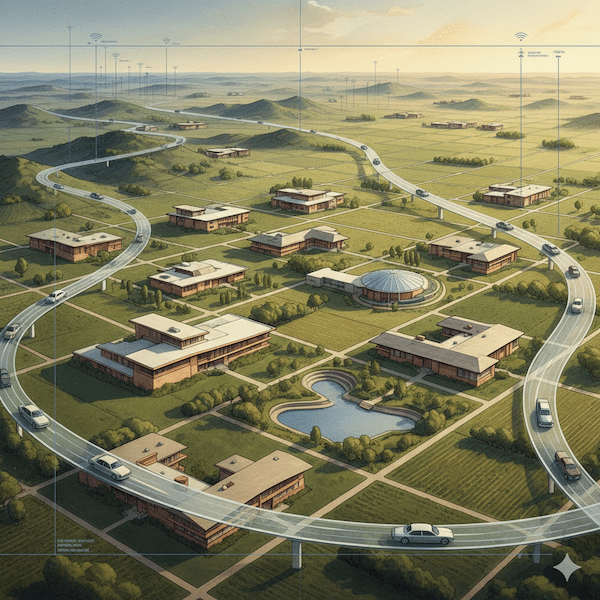

Lake Toya and its surrounding road. A giant "ring" created by nature.

Strategy 1: Road restructuring as "profitable infrastructure"

Just as Vienna turned the remains of its city walls into assets through an "urban expansion fund," the roads along Lake Toya need to undergo a paradigm shift from being merely "travel routes that require management costs" to "profit-generating investment targets."

Currently, road maintenance costs are a major financial burden for many local governments in Japan. However, following the example of Vienna, it is possible to reconsider the privileged location of a road (lakeside) as "capital" itself.

For example, local governments and DMOs (regional tourism organizations) could take the lead in consolidating the rights to unused land with good views and abandoned facilities. They could then formulate a landscape design code for the entire area (including height restrictions and consistent color tones), and offer long-term land leases and tax incentives to private developments that fit the code (foreign luxury hotels, villas for the wealthy, satellite offices). The profits from this could be reinvested not simply in road repairs, but in developing "public spaces of outstanding quality (such as observation terraces and art installations)."

Strategy 2: Mobility revolution (from cars to people and bicycles)

Even more noteworthy are the current trends in Vienna. Improvements to bicycle traffic on the Vienna Ring are currently under discussion and planning, with adjustments ongoing with a view to implementation after the election. Large-scale bicycle infrastructure development has been announced for the entire city until at least 2025, and the changes in urban structure are an irreversible trend.

This concept can also be applied to Lake Toya. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism's National Cycle Route (NCR) system is already in operation, and designated routes exist. How this is positioned around Lake Toya needs to be determined in accordance with the official policies of the Hokkaido Cycle Route Council, etc., but it is clear that simply marking out lanes for bicycles is not enough.

Like Vienna, we should boldly restrict automobile traffic in specific sections (such as the center of a spa town or a scenic spot) and create "premium rings" where pedestrians and slow mobility (bicycles and electric kick scooters) play a leading role. This will shift from sightseeing that simply passes through by car to sightseeing that involves walking around on foot, feeling the breeze and light. Reducing travel speeds from 40 km/h to 15 km/h will extend stay times, create more spending opportunities, and ultimately lead directly to an increase in average customer spending.

Strategy 3: Spatialization of stories (geopark narrative)

Finally, there is the perspective of "relational design." Vienna used its architectural style to express the "ideal of empire." So, what should Lake Toya say?

This is undoubtedly the "heartbeat of the living earth (Lake Toya-Mount Usu UNESCO Global Geopark)" and "coexistence with Ainu culture." Existing road signs and guardrails will be replaced from standard civil engineering standards with designs and materials that evoke the volcano's geological layers and lake water. The observation deck will be redeveloped not just as a photo spot, but as landscape architecture that allows visitors to experience the energy of past eruptions.

Creating a space where visitors can feel the deep story (narrative) of the place just by visiting is the most powerful branding method to differentiate a region from others and become a tourist destination of choice.

Conclusion: Remove invisible walls and design circulation

In Vienna in 1857, the biggest obstacle to the city's development was its physical city walls. The greatness of Emperor Franz Joseph I lay in his ability to change the perception of the walls from something that needed to be protected to something that should be torn down and utilized.

The walls we face today are not physical walls. They may be walls of the mindset of "following precedent," walls of the system created by "vertically divided administration," or walls of the fixed idea that "roads are for cars."

Vienna's success story teaches us that cities can be dramatically regenerated without relying on tax revenue, if they can redefine the value of existing assets (even negative legacies) and invent a system in which the public and private sectors work together to share risks and rewards.

Maximizing capital and beautifully redesigning the relationships between people and nature, and between people and history. The torch of urban regeneration that was lit in Vienna 170 years ago now awaits us, in a different form, on the frontier of Toyako, Hokkaido.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: About National Cycle Routes

- Vienna Tourist Board: History and Architecture of the Ringstrasse

- Ministry of the Environment: Japan's National Parks, Shikotsu-Toya National Park

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.