〜A massive urban experiment that visualizes the "power of the gaze"〜

*This article is based on official documents and historical documents as of January 2026.

As Robert Mumford said, "A city is the 'greatest concentration of power and culture' of a community" (The Culture of Cities, 1938), and the shape of the city we live in reflects the way it was governed at the time it was built.

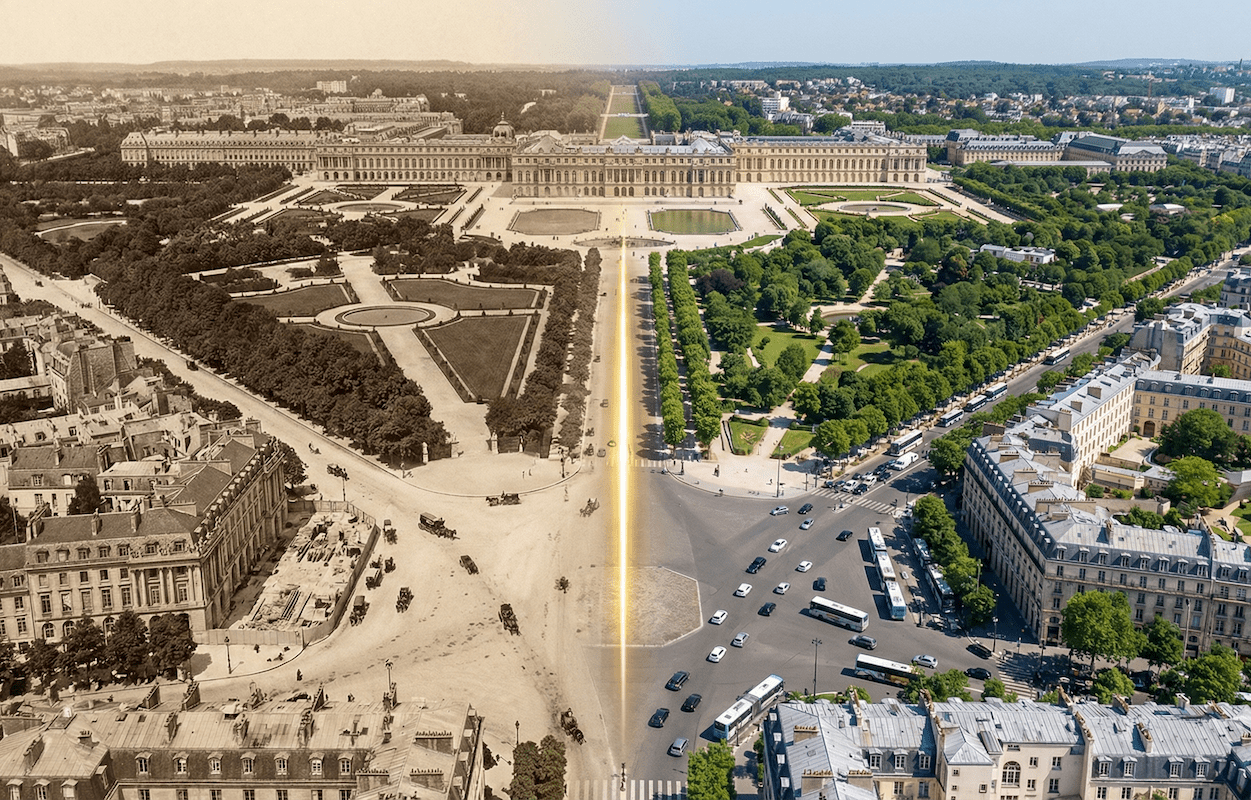

Located about 20 kilometers west of Paris, France, the Palace of Versailles is more than just a magnificent royal residence or tourist destination. It was an extremely sophisticated and cool-headed "experimental laboratory for urban planning" built by Louis XIV, the Sun King, at the height of absolute monarchy in the late 17th century, in order to exercise complete control over the land, nature, and people.

In particular, the three huge tree-lined avenues that radiate out from the palace's "King's Bedroom" as their center point and reach out into the horizon leave a strong trace of their heritage in the framework of the cities in which we live today - the streets of Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States, and Odori Park in Sapporo, Hokkaido.

First of all, why did those in power seek a "straight road" so badly? And what significance does this classic approach have in modern Japanese regional cities, where population decline and calls for environmental symbiosis are being made?

In this article, we dissect the enormous infrastructure of Versailles and unravel the lineage of urban design that transcends time and space, leading to the urban development of Toyako Town in Hokkaido.

1. The Gaze of Absolute Monarchy: The Axis of Infinity that Makes Power Visible

Control through "seeing" as depicted by the genius Le Notre

In 17th century France, the land of Versailles was the site of an ambitious project that involved filling in vast marshes, clearing forests, and geometrically conquering nature. The man at the center of this project was landscape architect André Le Nôtre.

Having studied perspective and optics in the studio of the painter Simon Vouet, Le Nôtre elevated gardens from mere objects of appreciation to "political devices" that control space. The concept of "axis" was undoubtedly the most important thing he considered in his designs.

Specifically, he created a perspective that centered on the palace's "King's Bedroom" and continued to "infinity" through the Grand Canal on the western garden side.He then inverted this geometric order toward the "Ville" on the east side, applying it to urban space as well.

In other words, the road network radiating out from the palace as a vanishing point symbolizes that the king's residence is both the starting point and the end point of all traffic routes. Here, the relationship between the "viewing subject (the king)" and the "viewed object (his subjects and the land)" was fixed through the physical infrastructure of the roads. Without moving a single step, the king could extend his gaze to every corner of the land via the radial roads - this was the pinnacle of visual domination that Baroque urban planning aimed for.

▼[Map] The Palace of Versailles and the three radial roads (Trident) extending eastward

Functional Anatomy of the "Trident"

These three huge avenues are called "goose feet" (Patte d'oie) because of their shape, or "tridents" after the weapon of Poseidon, the god of the sea.

The "Place d'Armes" in front of the palace, where these converge, was not just a traffic intersection, but functioned as a system that sucked up the flow of people, goods, and information from all over France in three directions into the palace's "Court of Honor" like a giant funnel.

| Name of the main street | Main Functions and Roles | Spatial features and data |

|---|---|---|

| Boulevard de Paris (Avenue de Paris) |

The most iconic "Royal Road" is the direct physical link between the royal residence and the capital, Paris (Louvre Palace). It currently functions as prefectural road D910. | Width: approximately 97 m (318 ft)。 It had a complex cross section consisting of a central roadway, side roads, and promenades, and was lined with four rows of elm trees. |

| Boulevard Saint-Cloud (Av. de Saint-Cloud) |

Access to the North and Normandy. Forms the northern boundary of the Grande Écurie. | The skeleton of the northern part of the city (Notre Dame district). It is approximately 70m wide. |

| Boulevard de Sceaux (Avenue de Sceaux) |

Access to the south and main link to military areas such as Satory. | It forms the southern boundary of the Small Stables and continues towards Sceaux, where the residence of Inspector General Colbert was located. |

The 1671 Urban Planning Decree: The Origins of Modern Zoning

What is even more noteworthy is the fact that extremely strict zoning (use district system) was imposed around these huge infrastructures.

In 1671, Louis XIV issued a groundbreaking edict that provided land for free to the nobility and citizens, provided that they adhered to building standards. This edict included the following regulations, which are still relevant to modern urban planning:

- Height restrictions (unification of skylines):

The height of the building was stipulated to be no higher than the ground level of the palace's "marble courtyard", thus physically ensuring that the palace would always dominate the cityscape. - Unity of the facade:

The exterior of the building facing the road features uniform stone and brick materials and a uniform roof slope, creating a harmonious atmosphere that makes it appear as if the entire city is part of the palace.

As a result, the mansions of high-ranking aristocrats (hotels) were neatly arranged along the main streets, and the homes of townspeople and craftsmen, as well as markets, were systematically arranged in the blocks behind them, creating a "royal city" where dignity and everyday functions coexisted. This can be said to be the forerunner of modern-day "architectural agreements" and "district plans."

2. The DNA of the "axis" spreading around the world: from Washington to Sapporo

The model of the "Baroque Trident" established at Versailles was quickly imitated in urban plans around the world due to its overwhelming visual effect and symbolism of power.

Comparison of main street widths in major cities

To get an idea of how extraordinary the scale of Versailles was, compare it to a modern-day major street.

[Illustration] Comparison of widths of major streets around the world (approximate values)

*Each figure is an approximate width at a representative location.

Washington, D.C.

Pierre Charles L'Enfant, who designed the city of Washington, DC, the capital of the United States, grew up in France and was familiar with the garden culture of Versailles.

A distinctive feature of L'Enfant's plan is that he adopted a technique of "superimposing" Versailles-style radial roads (avenues) on a practical orthogonal grid (streets).

Pennsylvania Avenue (approximately 49 meters wide) serves as a symbolic axis connecting the two institutions of democracy: the Capitol and the White House.

Here, by visually connecting the "representative organs of the people" rather than the "royal" gaze, the grammar of the Baroque city was brilliantly transformed into a symbol of the Republic.

Odori Park, Sapporo

There is also an interesting example of a city in Japan that was influenced by Western urban planning: Sapporo, which was planned during the Meiji period.

Odori Park, which runs east to west through the city center of Sapporo, is 105 meters wide and has an overwhelming scale that surpasses even the Boulevard de Versailles. This was originally an open space created as a firebreak to prevent the spread of urban fires.

However, it has now evolved into a monumental landscape axis with the Sapporo TV Tower as its focal point, and by echoing the design of Moere Numa Park by Isamu Noguchi, it functions as a rare urban axis in Asia that captures the majestic scale unique to Hokkaido.

▼[Map] The fusion of radial roads and grids in Washington DC

The merits and demerits of radial road systems: An assessment in modern cities

The "radial road" system that originated in Versailles, while aesthetically perfect, poses both clear advantages and serious challenges for modern urban function.

[Advantages: overwhelming symbolism and appeal]

The biggest advantage is the clarity of the city structure. When you step onto a major street, you can always see the direction of the center (the palace, parliament building, square, etc.), so residents and visitors can intuitively understand their current location (improved wayfinding).

Furthermore, the "vista" effect of placing beautiful buildings at the end of long, straight roads elevates the city itself into a work of art, creating a powerful city brand and tourist resource.

[Disadvantages: Traffic congestion and pedestrian disruption]

On the other hand, a structure in which all roads converge at one point (the center) can become a fatal bottleneck in today's automobile society. At the Place d'Armes in Versailles and the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, vehicles flowing in from multiple boulevards intersect, causing chronic congestion and complex merging routes.

Furthermore, where radial roads and orthogonal grids intersect at acute angles, the land tends to become irregularly shaped, such as triangular (flatiron type), which reduces the efficiency of land use.

3. A look at Toyako Town, Hokkaido: Urban development using landscape as a resource

So far, we have looked mainly at large cities in Europe and the United States, but by changing the scale and purpose, the concepts of "axis" and "landscape control" can also be extremely effective tools in modern Japanese regional cities, especially tourist destinations.

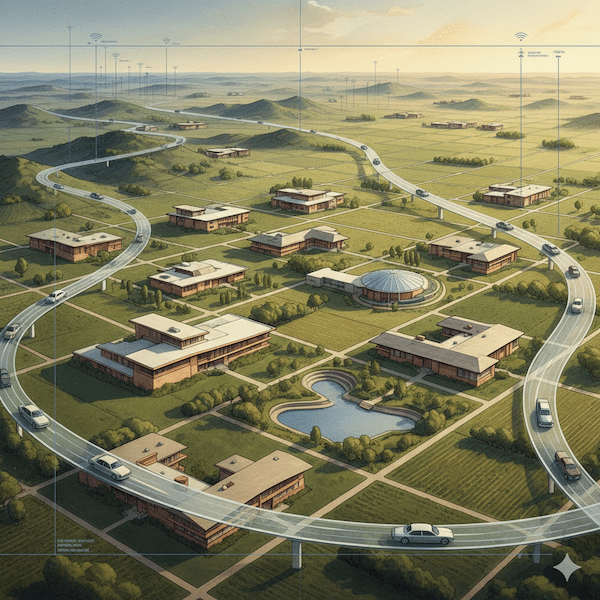

Here, we will analyze in detail the case of Toyako Town in Hokkaido, which hosted the 2008 summit and is focusing on landscape urban development.

Who is the Modern "King"? Reverence for Nature and Skylines

Toyako Town is pursuing "sustainable urban development" amid a declining population and aging society. Its urban master plan shows interesting similarities and contrasts with the Versailles-style structural theory.

It is worth noting that the Toya region was designated a "quasi-urban planning area" in 2009. This is a measure to prevent disorderly development (sprawl) even outside of urban planning areas, and to preserve the outstanding rural and lakeside landscapes that are characteristic of Hokkaido.

At Versailles, building regulations were imposed to ensure that buildings did not exceed the height of the palace in order to protect the authority of the king. So what is the "palace (absolute center)" in modern-day Toyako?

It is undoubtedly Mt. Yotei, Nakajima (Lake), and the overwhelming caldera topography itself.

Height restrictions in landscape planning (generally 13m to 20m or less in resort areas) and color guidelines are designed to prevent man-made structures from protruding and disrupting the natural skyline and ridgelines. The "height control" method, once used to protect the authority of the monarchy, has now been passed down as a "method" for protecting Hokkaido's irreplaceable natural landscape.

▼[Map] Routes leading to Lake Toya Onsen town and the lakeside

Illumination Street as an "axis of light"

In the Gardens of Versailles, fireworks were launched at nightly festivals (Fêtes), making the axis stand out in the darkness. This "spatial production with light" can also be seen in modern-day Toyako Town.

Toyako Onsen town is home to an "illumination street" and "illumination tunnel." This project involves decorating a street stretching over 70 meters from the center of the hot spring town to the lakeside with approximately 12,000 LED lights, creating a powerful "axis of light" at night that is even more powerful than the physical road.

This light trail will naturally guide the flow of tourists from the city to the lakeside (where the fireworks will be launched), transforming the road from a mere space for movement (Transport) into a place for dramatic experience (Experience) - this is nothing less than a modern and local implementation of the "spatial dramaturgy" that Le Nôtre intended for his gardens 350 years ago.

Conclusion: Historical "axis" for future sustainability

The history of "radial roads with urban functions," which began at the Palace of Versailles, began with political motivations to make power visible, and then passed through the post-Industrial Revolution era to improve transportation efficiency. In modern times, the city has shifted to a phase that emphasizes "quality of life (QOL)" and "harmony with the environment."

In fact, a dramatic project is currently underway on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, an extension of Versailles, to transform the street into an "Extraordinary Garden" by 2030. The plan, which involves halving the number of car lanes, significantly expanding pedestrian spaces and green areas, and restoring soil permeability, symbolizes a return from an "axis for cars" to an "axis for people and nature."

Toyako Town's scenic byways and landscape creation efforts, while on a different scale, are also positioned within this global trend in urban planning. Urban planning is not simply about arranging buildings and roads. It is about guiding the gaze of residents and visitors and designing memorable experiences.

350 years ago, the Baroque master Le Nôtre painted a gaze towards infinity. That spirit continues to live on today, changing shape and scale as a signpost illuminating the future of our city.

Related Links

- Official website of the Palace of Versailles (Château de Versailles)

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Hokkaido Regional Development Bureau Scenic Byway Hokkaido

- Toyako Town Landscape Plan (Hokkaido)

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.