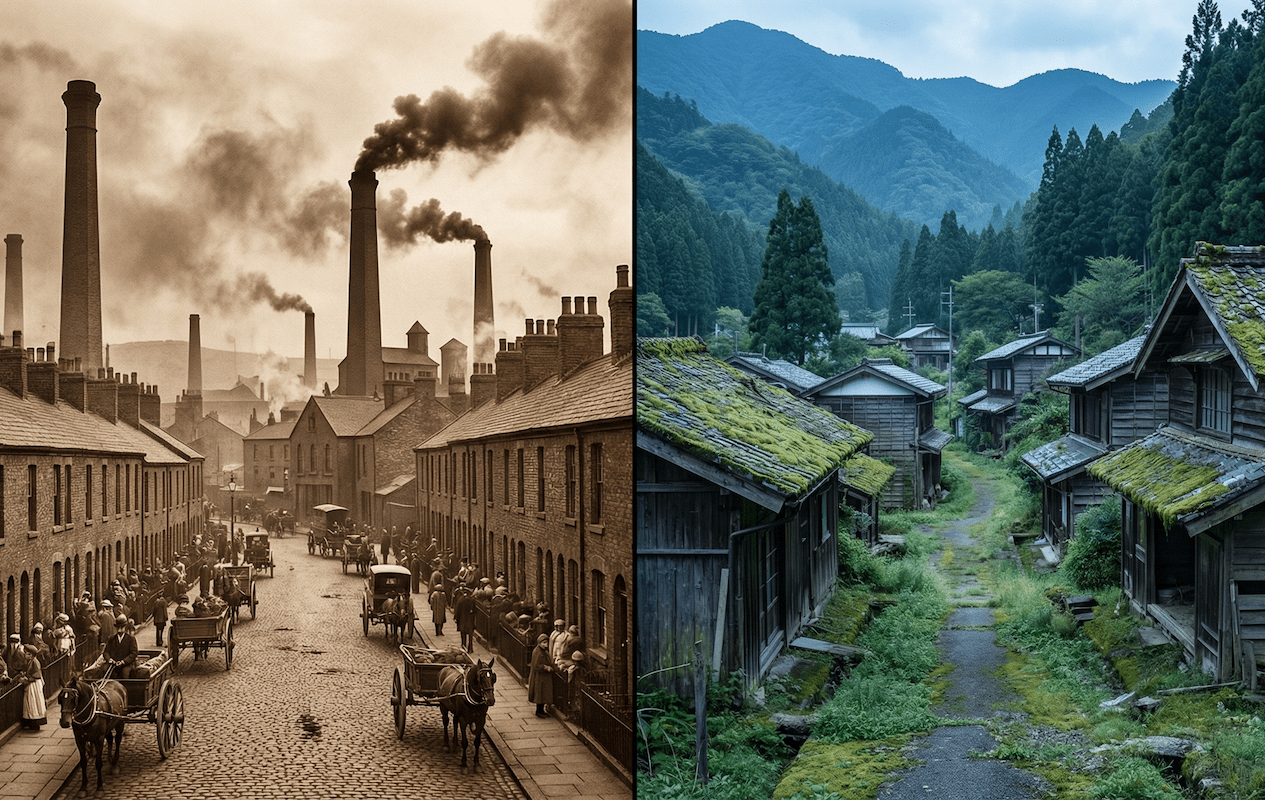

〜The "deadly overcrowding" caused by the 19th century British Industrial Revolution and the "silent slumization" that Hokkaido faces in the 21st century〜

*This article is based on information as of January 2026.

Cities are the most complex and contradictory giants ever invented by mankind.

While it is a source of wealth and innovation, if that balance is upset, it can transform into a stage for the most serious poverty and environmental destruction. Looking back at history, the Industrial Revolution that took place in Britain in the late 18th century was an event that exposed this paradox to its fullest extent. The technology of the steam engine tore humans away from the earth and threw them into the "high-density crucible" of the city.

Now, let's shift our perspective to the present day. In 21st century Japan, and particularly in regional cities in Hokkaido, we are facing a crisis with completely opposite vectors, but essentially the same roots. It is not "runaway growth" but "silence of degeneration."

Cities that once cried out in pain from population explosions and overcrowding are now suffering from hollowing out and the resulting sponge-like effects of population decline and aging. This article compares and analyzes the tragedy of "physical slum formation" that occurred in Manchester, England, in the 19th century, with the "silent slum formation (vacant house problem)" currently occurring in Toyako Town, Hokkaido. Drawing on the lessons learned from these two eras, we will attempt to interpret the "urban survival strategies" that will be necessary for the future.

1. Slumming in the Industrial Revolution: Cities of Overcrowding, Disease, and Death

The formation of industrial cities and the mechanism of population explosion

The Industrial Revolution was not just a series of technological innovations, but a fundamental rewriting of the rules of human habitation: where and how humans live and die.

At the end of the 18th century, improvements in the steam engine and the mechanization of looms made it necessary to concentrate factories in specific locations with power sources. As a result, traditional home-based craftsmanship collapsed, and rural people who lost their jobs flocked to cities like an avalanche. However, this migration was by no means planned. City governments at the time lacked the very concept of "urban planning" to accommodate such a large influx of people.

Manchester, England, was the center of the Industrial Revolution. This place was once shrouded in factory smoke.

In order to cram the maximum number of people onto the smallest of plots of land, landowners and speculative builders built a series of extremely low-quality tenement buildings known as "back-to-back" buildings. These houses were literally built back to back, with almost no ventilation or light, and no backyards or separate toilets. The very spatial structure of the city was distorted by the principles of maximizing profits and minimizing living expenses. It was this disorderly development that directly triggered the formation of slums.

Statistics reveal the "urban penalty"

The harshness of the urban environment at the time is not merely a subjective description, but is also unequivocally supported by statistical data on mortality rates. The phenomenon known as the "urban penalty" in urban economics and historical demography was extremely evident in 19th-century Britain.

*This shows that the infant mortality rate in industrial cities was significantly higher than that of the capital, London.

As the graph above shows, at that time in Liverpool, the rate of pre-first-year mortality was 21.0 per 100 live births (1861–70), meaning that one in five children died before their first birthday.

Interestingly, while the number of deaths under one year of age tended to be high in rural areas, the survival rate after one year of age tended to be higher in rural areas. In contrast, in large cities, the water and food consumed by children after weaning were contaminated, so high mortality rates continued even in infancy. The Industrial Revolution did not "uniformly worsen infant mortality rates," but "widened regional health disparities."

2. The Enactment of the Public Health Act and the Beginnings of Modern Urban Planning

Chadwick's "Hygiene Idea" and a Paradigm Shift

Urban squalor and the spread of disease were no longer seen as merely a problem for the working class, but as a threat to the very existence of the nation. Cholera was spreading not only to slums but also to wealthy neighborhoods, spreading fear throughout society. It was at this time of crisis that Edwin Chadwick emerged.

Chadwick made his groundbreaking claims in his monumental 1842 report, The Sanitary Condition of the British Labouring Population.

"The cause of poverty is not the moral decay of the poor, but disease caused by unsanitary conditions."

This was a shift in logic that overturned the common sense of the time. Disease took away the family's breadwinner, which in turn led to poverty and an increased burden on the poor tax. He argued that investing in public health measures such as drainage and cleaning was the most economically rational policy in the long term.

The Public Health Act of 1848

In 1848, against the backdrop of another cholera epidemic hitting Britain, the government finally enacted the Public Health Act 1848. This was an important milestone in the history of public health and marked a turning point in institutionalizing the development of urban sanitation infrastructure.

| Components | Contents and functions | modern significance |

|---|---|---|

| Central/Local Health Commission | In areas with a high mortality rate (over 23 cases per 1,000 people), there is a regulation that the central government can "impose" the installation of such facilities (although it should be implemented with caution). | Establishing a system in which the government is legally responsible for the "health" of its citizens. |

| Infrastructure Development Authority | Local governments are given the authority to issue bonds (loans) and provide water supply and sewerage services, road paving, etc. | Urban infrastructure development is defined as a "public work" and a financial scheme is introduced. |

| Specialist placement | Allows the appointment of public health physicians (initially voluntary) and surveyors. | The beginnings of urban management based on scientific knowledge (evidence). |

This law enabled cities to evolve from mere collections of buildings into "organic systems" that sustained life through underground pipes. It was during this period that the basic principle of public health, which is to "prevent disease by improving the environment" rather than "treat disease after it has occurred" (reactive treatment), was established.

3. Perspectives from Toyako Town, Hokkaido: Population decline and urban development in a "shrunken" state

The reality facing modern Japanese regional cities

While 19th-century Britain suffered from "growth and overcrowding," 21st-century Japan, particularly local governments in Hokkaido, are facing the opposite pressure of "shrinkage and depopulation." However, the two regions share surprisingly similar structural problems in terms of "deteriorating living environments" and "infrastructure maintenance crises."

Japan's population has been declining since peaking in 2008, with the rate of decline being particularly dramatic in rural areas. Unlike the period of high economic growth, when cities continued to expand outward, the country is now experiencing a "sponge urbanization" in which sprawling urban areas are becoming less dense. This is significantly reducing the efficiency of infrastructure maintenance and is the biggest factor putting pressure on the country's finances.

Toyako Town in Hokkaido has beautiful scenery and tourist attractions, but it also faces the problem of vacant houses scattered across the area.

Vacant House Problem: "Silent Slums" Spreading Across Japan

The increase in vacant houses can be described as a modern-day "slum development." Unmaintained houses directly worsen the living environment (QOL) of surrounding residents by increasing the risk of collapse, the growth of weeds and pests, encouraging illegal dumping, and the risk of arson.

This is by no means a localized problem in Toyako Town. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications' Housing and Land Statistics Survey (2023), the percentage of vacant homes in Japan's total housing stock (vacancy rate) is 13.8%, the highest ever recorded, and an extremely high level even by international standards. Toyako Town is also part of this larger trend throughout Japan, and is thought to be at risk of "silent slum development" at a rate similar to that of the nation as a whole.

*Japan's vacant house rate is nearly five times higher than that of the UK.

The vacancy rate in the UK (England) for all vacant dwellings will remain at approximately 2.81 TP3T (2023). In comparison, Japan's figure of 13.81 TP3T is clearly an abnormal situation. In many local governments, including Toyako Town, this structural gap in figures poses a threat to the sustainability of local communities. While the slums of the 19th century were a problem of "too many people and nowhere to live," modern Japan is in a phase where entire cities are decaying due to "there is space to live, but no one to live in it."

Financial constraints: Limits to maintaining infrastructure

While 19th century Britain struggled with borrowing to build future infrastructure, Toyako Town today is struggling with borrowing to maintain infrastructure it has built in the past.

The fiscal year 2024 budget summary data illustrates this harsh reality. Capital expenditures, particularly those for the water supply business, are expected to have a shortfall of approximately 259.13 million yen. This means that the costs of replacing aging water pipes and maintaining facilities cannot be covered by fee revenues and existing savings alone. Continuing to maintain water pipes and roads for vacant homes and communities scattered across a wide area, given the declining tax and fee revenues caused by a declining population, is tantamount to walking the path to financial collapse.

4. Comparative Data Analysis: Growing Pains and Shrinking Pains

Let us now compare the Industrial Revolution period of the 18th and 19th centuries (Manchester model) with a modern regional city in the 21st century (Toyako model), and organize the structural differences and similarities between the urban problems faced by each.

| Comparison items | Industrial Revolution (British cities) | Present day (Toyako Town, Hokkaido) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Explosive increase and influx (The rapid shift from rural areas to cities) |

Sustained decline and outflow (natural decrease + social decrease) |

| City Shape | Overcrowding/High density (Back-to-back housing clusters) |

Spongy and low density (Scattered vacant lots and vacant houses) |

| Major Health Risks | Infectious diseases and acute illnesses (cholera, typhus, high infant mortality rate) |

Chronic illness/social isolation (Diseases due to aging, lonely deaths) |

| Infrastructure status | "absence" (The pain I'm about to cause) |

"Aging and excess" (Unsustainable suffering) |

| financial structure | Issuing bonds for investment (Betting on future growth with a 30-year loan) |

Deficit compensation for maintenance (Capital deficit, fund withdrawal) |

What can be inferred from this comparison is a change in the "quality of death." Data from the Industrial Revolution period shows the physical violence of the environment directly killing people (through infectious diseases and pollution). In contrast, what Toyako Town is facing today is the "death of the community" caused by the gradual loss of social ties and economic foundations. While the former is acute and the latter is chronic, both are in agreement in that the "balance between infrastructure and population" has collapsed.

5. Conclusion and Outlook: Redefining Sustainable Living Spaces

The conclusion drawn from the detailed research and analysis in this report is that cities are systems of increasing entropy that, if left unchecked, will inevitably worsen living environments, and that constant "deliberate intervention" is required to stop this.

Nineteenth-century Manchester taught us that urban growth without infrastructure kills people, and today's Toyako Town shows us that urban decline without sustainable infrastructure also threatens the lives of its residents in other ways.

To carve out a future for Toyako Town, and other regional cities in Japan facing similar challenges, we need a new "urban planning for shrinkage" approach comparable to the 19th century's "public health planning for growth."

Specifically, the town must face up to the reality that it is impossible to manage all the vacant houses scattered throughout the town, and promote "residential guidance" that concentrates government services and infrastructure in specific locations, and "planned withdrawal" from areas that are difficult to maintain. This is the process of using a small "sponge" to restore density.

Social ownership and the integration of tourism and lifestyle

Going further, it is also essential to update the legal system. Just as the 1848 Act made it possible to lay pipes on private property and forcibly clean up the property, we must also allow for stronger public intervention in the modern era in the case of "unmanaged vacant houses" (through forced demolition, temporary custody of ownership, and the establishment of usage rights, etc.). Individual property rights are important, but when they threaten the survival of the entire local community (public interest), we cannot avoid the discussion of "socialization of ownership," which states that certain restrictions should be placed on these rights.

Furthermore, with no hope of an increase in the permanent population, Toyako Town's tourism potential is its greatest asset. The town should strengthen mechanisms for tourists and dual-base residents to renovate and utilize vacant homes (such as an expanded version of the "Challenge Shop") and build a model that converts external vitality into internal infrastructure maintenance costs.

Conclusion: Towards a "new design" that embraces maturity and downsizing

In the 19th century, humanity attempted to overcome the problem of slums through the steam engine and legal systems. In the 21st century, we are faced with the question of how to maintain dignified "places to live" amid a declining population and shrinking economy.

The answer lies in a new, cool-headed, human-centered urban design that discards the success stories of the past, accepts maturity and shrinkage, and embraces the need for economic growth. "Public health is an economic issue." These words, left behind by Chadwick, remain true even in today's measures to combat vacant houses.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Special website for measures against vacant houses

- Toyako Town, Hokkaido: Comprehensive Strategy for Revitalizing Towns, People, and Jobs

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: About the Water Supply Business

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.