〜A new urban development theory that goes beyond physical urban planning and is based on "relational design"〜

*This article is based on information as of January 2026, and references historical documents and the latest urban planning data.

"I want to open new streets, sanitize neighborhoods deprived of air and sunlight, and bring health to the people."

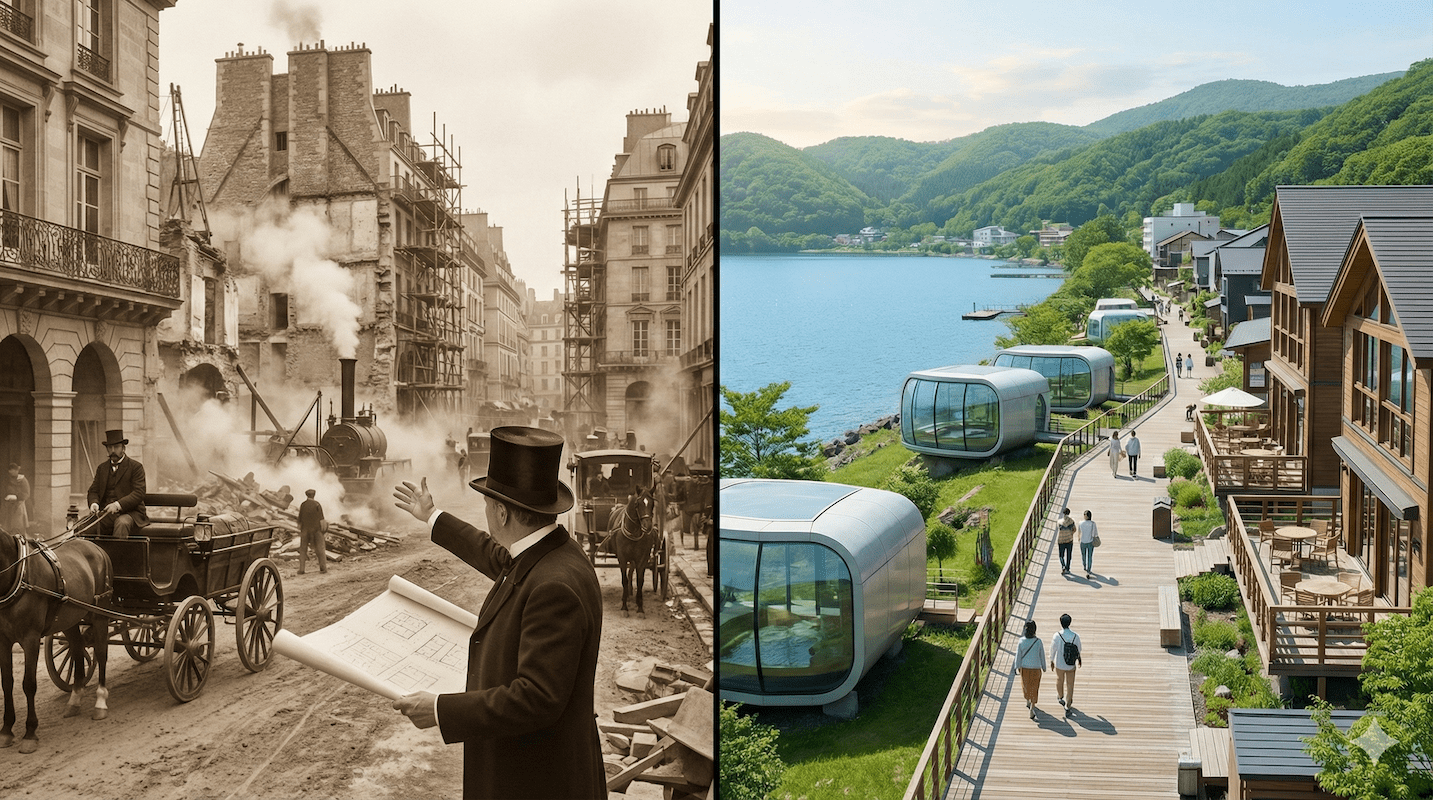

Around 1850, Napoleon III, Emperor of the Second French Empire, spoke these words, expressing his desire for urban reform. Paris at the time was not the sophisticated "City of Light" that we imagine today. It was a "City of Mud" with its labyrinthine, narrow alleys that had existed since the Middle Ages, a rapid influx of population due to the Industrial Revolution, and a lack of sewage systems that led to overflowing filth and rampant cholera.

In response to this urban crisis, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Prefect of the Seine, carried out a thorough surgical operation using state power - a massive project that would later be called the "Great Renovation of Paris (Travaux haussmanniens)." The destruction and creation he oversaw established the standard for modern cities, but it also remains one of the most violent and authoritarian examples in the history of urban planning.

Fast forward to the 21st century. Today's Paris is based on the framework established by Haussmann, but is trying to move away from an automobile-centric urban structure. Meanwhile, Japan, particularly regional cities like Hokkaido, is facing a completely different "disease": a declining and aging population, and new prescriptions are needed.

This article begins with a cold-hearted data analysis of the major renovation of Paris in the 19th century, then connects the dots between the "15-minute city" concept currently being promoted in Paris and the urban development project in Toyako Town, Hokkaido. From physical "destruction" to social "editing," it paints a map of how cities should change in the future.

1. Surgery on the "City of Mud": A Complete Look at Ottoman Destruction and Creation

The Demolition Company Called the Nation

The essence of the Great Remodeling of Paris, which took place between 1853 and 1870, was the largest-scale "artificial reconstruction" of the huge urban organism in history."The Demolisher"The demolition was so thorough that it earned the city the nickname "The Great Demolition," and it physically destroyed the medieval old town, including the Île de la Cité.

Why was such drastic destruction necessary? The following multiple factors were behind the destruction:

- Sanitation crisis:The cholera epidemics of 1832 and 1849 were beginning to be scientifically recognized as being caused by narrow streets and unsanitary conditions.

- Political/military motives:The maze-like alleys were ideal for citizens to build barricades and were a breeding ground for revolutions, so Napoleon III wanted straight, broad streets that would allow troops and artillery to be deployed quickly and with clear lines of fire.

- Economic needs:The development of the railway network led to a dramatic increase in the influx of people and goods into Paris, but the medieval road network created a bottleneck in distribution, hindering the growth of the capitalist economy.

The "geometry of power" as seen on a map

Take a look at the map below. You can see 12 avenues radiating out from the Arc de Triomphe (now Place Charles de Gaulle) in the center. These are not naturally occurring streets, but a "geometry of power" that was calculated as if drawn with a ruler.

Haussmann mobilized a huge amount of money for this renovation. According to the budget at the time, an investment of 2.5 billion francs was made (the conversion into modern currency is uncertain and there are various opinions). What is particularly noteworthy is that he brought modern financial techniques (leverage) to urban management by taking on huge debts in anticipation of "increased tax revenues due to future rises in land prices."

| Comparison items | Great Renovation of Paris (19th century) | Contemporary Paris (21st century) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic philosophy | Physical expansion and efficiency (Straight roads for carriage traffic, logistics, and military) |

Improving quality of life and adapting to the environment (Reorganizing spaces for pedestrians and bicycles) |

| Infrastructure development | Expand sewerage from 142km to approximately four times that (approximately 570km) (Modernization of Sanitation and Invisible Infrastructure) |

Approximately half of the on-street parking (up to 60,000 spaces) will be converted (Transition to decarbonization and visible infrastructure) |

| Funding and Risk | Strong criticism of debt and accounting practices (Speculative development in anticipation of profits from rising land prices) |

Utilizing and modifying existing stock (Sustainability-focused budget allocation) |

*You can view the table by scrolling horizontally.

2. Paradigm Shift: From Expansion to "Relationship Design"

From Fluidity to Stagnation: The Impact of the 15-Minute City

Haussmann's vision was a city of "circulation," where people and goods flowed smoothly like blood. However, the current mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, is pursuing a policy that reverses that direction 180 degrees.

She holds up"15 minute city" (Ville du quart d'heure)The initiative is based on a concept proposed by Professor Carlos Moreno of Sorbonne University, which aims to create an urban structure in which all daily activities, such as work, school, medical care, shopping and cultural activities, can be accessed within 15 minutes by foot or bicycle from one's home.

Specifically, roads that Haussmann expanded for automobiles (such as Rue de Rivoli) are now closed to regular vehicles (only authorized vehicles are allowed) and converted into bicycle lanes and squares. This re-weaves the context of community that was once discarded for the sake of "efficiency," and shifts the axis of evaluation of the city from "how fast you can move (Speed)" to "how richly you can stay (Quality of Time)."

"Space redistribution" seen through data

The graph below shows how the allocation of road space in Paris has changed in recent years. It shows how the car-oriented space established in the 20th century is rapidly being opened up to people.

Changes in urban space occupancy rate (conceptual diagram)

*Image based on target reductions for on-street parking spaces

*You can view the graph by scrolling horizontally.

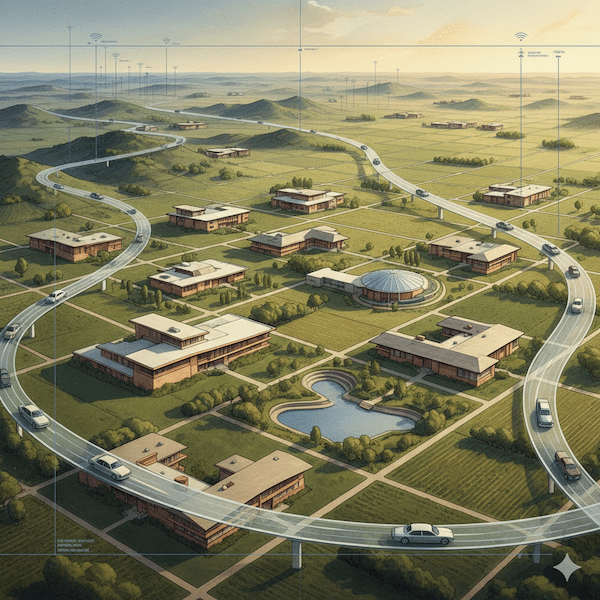

3. The Fight for Editing in Toyako Town, Hokkaido

Breaking away from the colonial grid

Let's shift our perspective to Japan. The history of urban development in Hokkaido has been heavily influenced by Haussmann's Paris and the modern urban technology of the same era. During the Meiji period, under the advice of Horace Capron, an advisor to the Hokkaido Development Commission, Hokkaido cities, including Sapporo, were built using a method of laying out grid-like streets in the wilderness. The surveying techniques and zoning concepts are similar to Haussmann's methods, which were the global standard of the time.

However, these "too wide" roads are a modern-day problem. They leave no barriers to the cold winter wind, are out of scale for pedestrians, and require enormous maintenance costs (such as snow removal). As a result, they have led to urban sprawl, making it impossible to live without a car.

With this historical background in Hokkaido, Toyako Town, which is facing a declining population, has a clear strategy to adopt. This is not to "destroy for expansion" as in the Ottoman Empire, but to utilize existing assets."Editing for quality"is.

On-site: The potential of Lake Toya hot springs

Toyako Town has overwhelming resources, such as a beautiful caldera lake and hot springs, but it is facing challenges such as the aging of a huge hotel built in the Showa period and the hollowing out of its shopping district. The area on the map below is the central area where the revitalization project will take place.

Toyako Town is currently promoting democratic landscape management centered on a "Landscape Ordinance." What's important here is that while Haussmann's top-down approach forced uniformity in building heights and materials, Toyako Town's ordinance explicitly calls for "cooperation" with residents and businesses in Article 1. This marks a clear shift from "urban planning" to "machizukuri."

This is a top-down approach led by government and experts, as exemplified by the Haussmann method. It exercises strong authority, such as the right of eminent domain, and prioritizes "hardware development" such as road widening and large-scale construction. While this has dramatic effects on economic efficiency and sanitation improvement from a macro perspective, it carries the risk of destroying existing resident communities.

It is a bottom-up approach that has attracted global attention as a uniquely Japanese concept. Residents, businesses, and government work together on an equal footing, building consensus through dialogue such as workshops. The emphasis is on the "software," such as community building, landscape preservation, and the inheritance of local identity. It places value on the process itself rather than on physical completion.

Proposal: Toyako version of "15-minute resort"

If we were to translate contemporary Parisian knowledge locally and apply it to Toyako Town, it would be"15-minute resort"The concept will be to transform from a transit-based tourist destination into a lifestyle-based tourist destination.

-

Walkable lakeside space:

Automobile traffic will be dramatically curbed on the main street along the lake, transforming the road space from a place for cars to a place for people to stay and enjoy the lake, a repeat of what Paris did with Rue de Rivoli. -

Creating space through Smart Shrink:

Rather than simply clearing unused vacant houses and abandoned hotels, we will convert them into pocket parks, foot baths, and community vegetable gardens to increase community contact. This is a reversal of the idea that by reducing the number of buildings, we can actually improve the "quality" of the space. -

Infrastructure visualization and aesthetics:

Just as Haussmann boasted about his sewage system as the "organs of the city," Lake Toya's water purification system and hot spring heat utilization infrastructure will be turned into tourist attractions as an "ecomuseum." This is a strategy that turns the backyard into the front stage.

Conclusion: Modern Ottomans don't ride bulldozers

In the 19th century, Paris established the standard for modern cities through destruction. Haussmann's achievement was in his bold updating of the city, based on his understanding of the city as a single, gigantic system.

However, the leadership needed in Toyako Town, Hokkaido in the 21st century in which we live is not physical renovation with bulldozers, but "editing skills" that carefully reweave existing resources based on data and through repeated dialogue with residents.

The "light and air" that Haussmann sought could be rephrased in modern terms as "the warmth of community" and "a sustainable environment." The era of physically widening roads is over. From now on, the true urban transformation will depend on "relationship design," which involves how we use existing roads and with whom we walk.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: Public-Private Partnership Urban Development Portal Site

- Toyako Town: Overview of the Landscape Plan and Landscape Ordinance

- Paris.fr: La ville du quart d'heure

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.