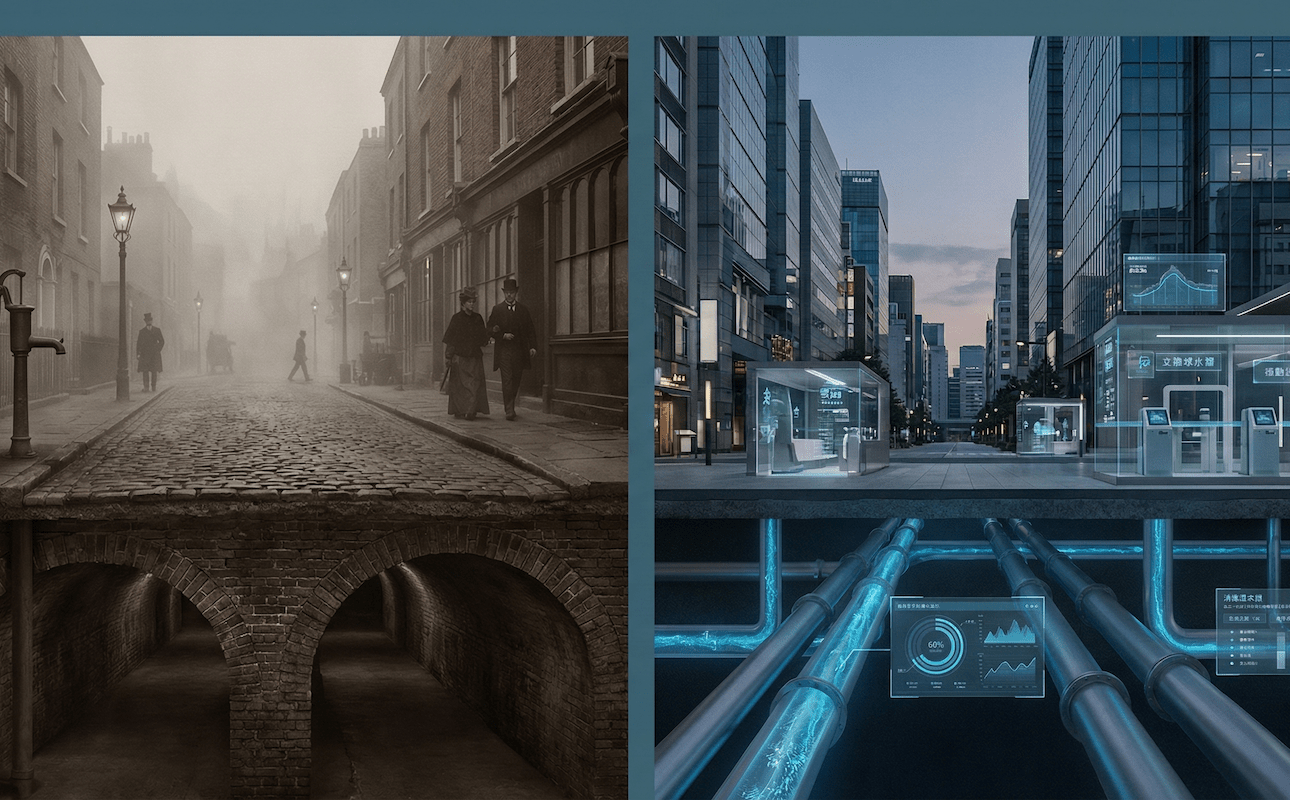

〜Fear of cholera, a 19th-century pandemic, created a city's immune system〜

*This article is based on information as of January 2026, and references historical documents and the latest data from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

When you turn on the tap, clear water flows out. When you turn the lever, the filth disappears from sight in an instant.

This platform known as a "clean city," which we enjoy every day without even questioning it, did not emerge spontaneously. It was designed as a painstaking response to the terrible "fear of death" that humanity once faced.

Cholera was a pandemic that shook the world in the shadow of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. Its ferocity revealed just how fragile the organisms of cities were at the time. When we trace the origins of modern urban planning, we find that it was not simply a matter of rezoning land, but rather a massive surgical operation that, from a medical perspective, physically implanted a circulatory system (water supply system) and an excretory system (sewerage system) into the ailing patient known as the city.

In other words, infrastructure is the city's "immune system" itself.

This article will explore the inseparable history of public health and urban development, from London's underground labyrinths to the opening of Japan to the world, and the future of our local communities. It will also delve deeply into the true nature of the assets we must protect in the modern age, when the silent crisis of aging is looming.

1. How the pandemic changed cities: Lessons from London's "Great Stink"

Let's turn the clock back to the 1850s. London, the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution, was thriving as the world's largest metropolis with a population of over 2.5 million. However, its reality was a pitiful state that could be described as a "glorious slum."

The city's metabolic capacity - its ability to process excrement - was completely overwhelmed by the rapidly growing population. At the time, London did not have a modern sewer system, and people collected waste in cesspools beneath their homes, which they then manually pumped out or simply dumped onto the streets or into storm drains.

As a result, the Thames, London's main river and drinking water source, had become a huge wastewater recycling system. Then, cholera, a deadly infectious disease originating from the Ganges River basin in India, struck.

"Location" Kills: John Snow and the Broad Street Pump

Cholera is a disease that causes severe diarrhea and dehydration within just a few hours of onset, leading to death due to the loss of fluids throughout the body. The rapid progression of the disease and the unknown cause of its spread led people at the time to fear it as the "invisible Grim Reaper."

At the time, the medical community was dominated by the "miasma theory," which held that disease was spread by "bad air" emanating from decaying matter. However, there was one doctor who boldly challenged this established theory: John Snow, the father of modern epidemiology.

When a cholera epidemic erupted in Soho in 1854, Snow suspected that the cause was not the air but the water. He used a groundbreaking data visualization technique at the time, plotting the locations of deaths house by house on a map.

▼ Current Broadwick Street (formerly Broad Street). The pump here was the source of the infection.

After investigating, Snow discovered a certain fact: the deaths were concentrated among users of a particular well: the "Broad Street Pump."

"Remove the pump handle."

The epidemic was dramatically contained the moment Snow persuaded the local government to physically stop using the pumps. This marked a historic turning point in urban public health management, marking a paradigm shift from vague "air purification" to scientific "water source management."

| Comparison items | Miasma Theory | Waterborne Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition of the cause | The "bad smell and bad air" emitted from decaying food carries disease | The hypothesis that contaminated "water" transmits disease |

| Urban Measures | Improving ventilation, cleaning streets, spraying perfumes and disinfectants | Separation of water and sewerage systems, protection of water sources, and physical isolation of wastewater |

The Great Stink that Moved Congress

However, scientific discoveries alone did not lead to the huge budget required for urban renovation. Ironically, it was the "discomfort" that struck politicians themselves that motivated them to undertake such a project.

In the summer of 1858, London was hit by a record heat wave. The heat wave caused a huge amount of sewage to pile up in the River Thames, causing it to rot and ferment, filling the whole of London with an unbearable stench. This is what has become known as the "Great Stink."

In the Houses of Parliament on the River Thames, MPs debated with handkerchiefs over their noses, soaked curtains in chloride of lime (a disinfectant) to stave off the stench, and even considered evacuating the building. Fearing for their lives and noses, Parliament passed the bill in just 18 days and authorized a massive sum of money (the 1858 Act gave them borrowing powers of up to £3 million) that rivaled the national budget at the time.

2. The Underground Revolution: Bazalgette's "Arteries" and "Veins"

In response to this crisis, Chief Engineer Joseph Bazalgette presented an ambitious blueprint to completely reshape London's underground.

Central to his plan was the concept of "Intercepting Sewers," a system in which the numerous small drainage channels flowing into the Thames would be "intercepted" by a huge main sewer system running parallel to the river, which would use gravity to transport wastewater downstream to remote areas rather than dump it into the river.

| Comparison items | [A] Traditional type (up to 1850s) | [B] Bazalgette System |

|---|---|---|

| basic principle | Gravity flow/discharge Discharge into the nearest river via the shortest route. |

Interception/transfer It prevents it from entering the river and transports it long distances outside the city. |

| power source | Gravity only (prone to clogging) | Gravity + Giant steam pump Sewage is pumped up at key points to maintain the flow rate. |

| Impact on cities | Groundwater contamination, foul odors, and the spread of disease | water quality improvement,Embankment RoadCreation of subways |

Bazalgette used 318 million bricks to lay a sewer network stretching 1,800 km in total. He also employed pioneering methods for modern integrated infrastructure development, filling in the marshes of the Thames to house the sewer pipes, building a new road (the Embankment) on top of it, and then laying the world's first subway underground.

The effect was dramatic. Below is an image of the change in the number of cholera deaths before and after the sewerage system was installed.

Approximate number of cholera deaths in London

(Undeveloped)

(Snow Survey)

(Partially operational)

*Only prevalent in the undeveloped East End area

(After completion)

3. "Korori" in Japan and the Water Supply System in the Early Modern Period

Cholera, which arrived in Japan at the end of the Edo period, was called "korori" (tiger-wolf dysentery) because of its similar pronunciation and high lethality.

"Someone who was healthy yesterday will die suddenly today."

The fear was so great that the death toll in Edo during the Ansei epidemic (1858) is estimated to be anywhere from tens of thousands to over 100,000 (there are various theories). People suspected it to be the work of monsters or poison brought in by foreigners, and society fell into panic.

For the Meiji government, frequent cholera epidemics were more than just a hygiene issue; they were a threat to the survival of the nation. Not only did the loss of labor force result in quarantine ships (stopping trade) due to the outbreak of infectious disease pose a fatal threat to the Japanese economy, which was rushing to modernize.

Furthermore, in order to revise the unequal treaties, Japan had to prove to the Western powers that it was a civilized country capable of managing sanitation.

Given this background, modern urban planning in Japan began with the development of vital infrastructure, namely the water supply system, rather than the construction of roads and squares as in Europe and the United States.

The pioneer of this was the Yokohama Waterworks, completed in 1887 (Meiji 20). Under the direction of British engineer Henry Spencer Palmer, this project drew water from the upper reaches of the Sagami River, and was Japan's first modern waterworks, becoming a model for subsequent urban sanitation projects.

▼ Japan's first modern waterworks was installed in Yokohama (around Nogeyama Water Reservoir). This marked a turning point in the history of water in Japan.

Hokkaido: Infrastructure as a Breakwater

The situation was dire in Hokkaido as well. Hakodate and Otaru, which served as hubs for the mainland, were on the front lines of cholera, bringing people and goods with them. During the 1886 epidemic, many people died in Hakodate.

In response to this, Hakodate completed a modern waterworks system, the second in Japan after Yokohama, in 1889. This was an investment that should have been prioritized above all else, as Hakodate at the time was to function as an international trading port and as a "breakwater against epidemics" for the development of Hokkaido.

4. Modern Issues: The Cry of Aging "Invisible Assets"

Thanks to the great investments made by our predecessors, modern Japan has one of the world's best public health standards. There are very few countries in the world where you can drink the water straight from the tap.

However, we are now facing a new, more static and serious crisis: aging infrastructure.

Sewerage and water pipes that were laid all at once during the period of rapid economic growth are now all reaching the end of their service life (generally 50 years). The graph below shows a forecast of the future length of sewerage pipes 50 years after construction.

Estimated length of sewerage pipes that are 50 years old after construction

Source: Created based on materials from the National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management (as of the end of FY2019)

Explosive growth:

Currently, only a few percent of the total pipes are deteriorated, but in 20 years, approximately 30 to 40 percent of the total length will be in danger of flooding. The increased risk of road collapses and the rising cost of renewal could become a "time bomb" for local governments struggling with declining tax revenues due to population decline.

If the challenge in the 19th century was "how to create (construction)," our challenge in the 21st century has shifted to "how to protect and wisely fold (maintain and reorganize)."

It is no longer possible to upgrade all infrastructure equally, as was the case in the days of steady growth. We are being forced to make the painful decision to "select and focus."

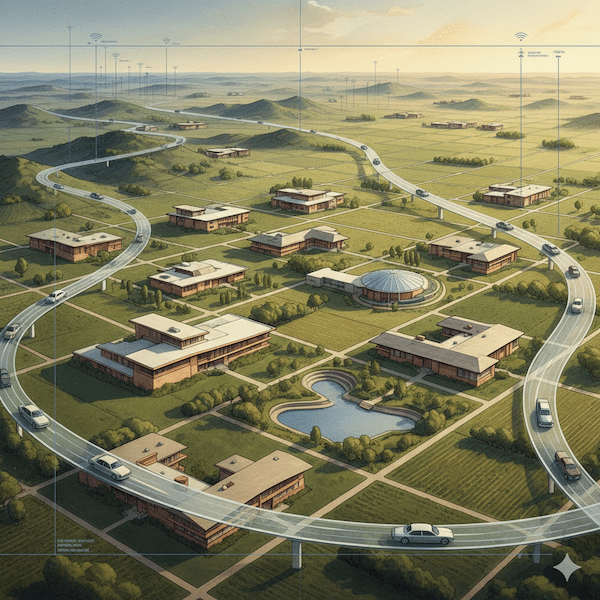

5. Suggestions for regional revitalization: A perspective from Toyako Town

So what does this historical context suggest for a place like Toyako Town, Hokkaido?

The sewerage coverage rate of Toyako Town is approximately 86.0% (as of the end of fiscal year 2022). This is significantly higher than the national average (approximately 81%) and compared to towns and villages of similar size in Hokkaido. One of the reasons for this is likely that Toyako Town has maintained a high level of awareness of environmental improvement as the host city of the 2008 Hokkaido Toyako Summit.

▼ Toyako Town. To protect the closed waters of the caldera lake, advanced wastewater treatment is required.

However, the cost of maintaining the pipelines connecting settlements scattered over a vast area is enormous. In addition, as the town is located at the foot of Mount Usu, an active volcano, there is also the risk of pipeline damage due to tectonic movements.

What is needed here is a perspective that reconsiders "clean water" not simply as a sanitation facility, but as a "capital" that creates economic value.

| perspective | Conventional wisdom | Future Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| The value of infrastructure | Commonplace public services (cost) |

Source of tourism resources and brands (Investments/Assets) |

| Maintenance method | Uniform sewerage pipe connection (Network expansion) |

Smart Shrinkage Conversion to combined treatment septic tanks in sparsely populated areas |

Downsizing: Evolution

In a situation of population decline, it will be necessary to shift from laying pipes to treating wastewater at each household (using septic tanks, etc.), in other words, to downsize infrastructure. This is not a "setback."

In the event of a disaster (especially a crustal movement such as an eruption), a networked infrastructure that is connected like a mesh is vulnerable as a disruption in one area can spread to the entire system.In contrast, an autonomous decentralized system is resilient from the perspective of risk dispersion.

Humanity once centralized city management to prevent cholera, but perhaps it is now time for us to once again embrace the wisdom of "decentralization" for the sake of sustainability.

Conclusion: Passing on the city's "immune system" to the next generation

When John Snow removed the handle of the pump and Bazalgette laid bricks underground in 19th century London, they weren't just curing a disease; they were implanting an "immune system" into the patient: the city.

We at KAMENOAYUMI think about this.

The mission of modern urban planning (city development) is not just to create spectacular buildings and events on the ground, but to properly understand the value of the "life support system" that lies beneath our feet and to hand it over to the next generation in a sustainable way.

Because infrastructure is "invisible," its importance tends to be overlooked until a crisis strikes. However, just as the continuous circulation of water is a prerequisite for life, the healthy circulation of infrastructure is an absolute prerequisite for the survival of regional cities.

Learning from the horrors of the past and preparing for future risks - it is in these steady efforts that true regional revitalization lies.

Related Links

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism: History and Role of Sewerage – From Ancient Times to the Present

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: Current Status and Issues of Water Supply Administration – Measures to Address Aging Infrastructure

- Toyako Town: Sewerage Business Management Strategy – Towards Sustainable Operation

Inquiries and requests

We help solve local issues.

Please feel free to contact us even if it is a small matter.